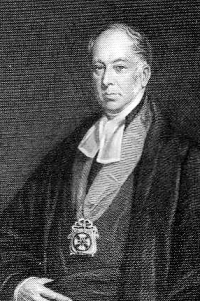

Richard Whately

Richard Whately | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Dublin Bishop of Glendalough Primate of Ireland | |

| |

| Church | Church of Ireland |

| Diocese | Dublin and Glendalough |

| In office | 1831–1863 |

| Predecessor | William Magee |

| Successor | Richard Chenevix Trench |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 23 October 1831 by Richard Laurence |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 February 1787 |

| Died | 8 October 1863 (aged 76) Dublin, County Dublin, Ireland |

| Buried | Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin |

| Nationality | English |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Whately |

| Children | 5 Philosophy career |

| Education | Oriel College, Oxford (B.A., 1808) |

| Institutions | Oriel College, Oxford |

Main interests | Theology, logic |

Notable ideas | Erotetics |

Richard Whately (1 February 1787 – 8 October 1863) was an English academic, rhetorician, logician, philosopher, economist, and theologian who also served as a reforming Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin. He was a leading Broad Churchman, a prolific and combative author over a wide range of topics, a flamboyant character, and one of the first reviewers to recognise the talents of Jane Austen.[1][2][3]

Early life and education

[edit]Whately was born in London, the son of the Rev. Dr. Joseph Whately (1730–1797). He was educated at a private school near Bristol, and at Oriel College, Oxford, from 1805. He obtained a B.A. in 1808, with double second-class honours, and the prize for the English essay in 1810; in 1811, he was elected Fellow of Oriel, and in 1814 took holy orders. After graduation he acted as a private tutor, in particular to Nassau William Senior who became a close friend, and to Samuel Hinds.[3][4]

Career

[edit]University of Oxford

[edit]In 1825, Whately was appointed principal of St. Alban Hall at the University of Oxford, a position obtained for him by his mentor Edward Copleston, who wanted to raise the notoriously low academic standards at the Hall, which was also a target for expansion by Oriel.[3]

Whately returned to the University of Oxford, where he had seen the social impact of unemployment on the city and region.[5]

A reformer, Whately was initially on friendly terms with John Henry Newman. They fell out over Robert Peel's candidacy for the Oxford University seat in Parliament.[6]

In 1829, Whately was elected as Drummond Professor of Political Economy at Oxford in succession to Nassau William Senior. His tenure of office was cut short by his appointment to the archbishopric of Dublin in 1831. He published only one course of Introductory Lectures in two editions (1831 & 1832).[7]

Archbishop of Dublin

[edit]Whately's appointment by Lord Grey to the see of Dublin came as a political surprise. The aged Henry Bathurst had turned the post down. The new Whig administration found Whately, who was known at Holland House and effective in a parliamentary committee appearance speaking on tithes, an acceptable option. Behind the scenes Thomas Hyde Villiers had lobbied Denis Le Marchant on his behalf, with the Brougham Whigs.[8] The appointment was challenged in the House of Lords, but without success.[7]

In Ireland, Whately's bluntness and his lack of a conciliatory manner caused opposition from his own clergy, and from the beginning he gave offence by supporting state endowment of the Catholic clergy.[clarification needed] He enforced strict discipline in his diocese; and he published a statement of his views on Sabbath (Thoughts on the Sabbath, 1832). He lived in Redesdale House in Kilmacud, just outside Dublin, where he could garden. He was concerned to reform the Church of Ireland and the Irish Poor Laws.[7] He considered tithe commutation essential for the Church.[9]

Irish national education 1831 to 1853

[edit]In 1831, Whately attempted to establish a national and non-sectarian system of education in Ireland, on the basis of common instruction for Protestants and Catholics alike in literary and moral subjects, religious instruction being taken apart.

In 1841, Catholic archbishops William Crolly and John MacHale debated whether to continue the system, with the more moderate Crolly supporting Whately's gaining papal permission to go on, given some safeguards.[10] In 1852, the scheme broke down due to the opposition of the new ultramontanist Catholic archbishop of Dublin, Paul Cullen, who would later become the first Irish prelate named Cardinal. Whately withdrew from the Education Board the following year.

During the famine years of 1846 and 1847, the archbishop and his family tried to alleviate the miseries of the people.[7] On 27 March 1848, Whately became a member of the Canterbury Association.[11] He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1855.[12]

Personal life

[edit]After his marriage to writer Elizabeth Whately (née Pope) in 1821, Whately lived in Oxford. He gave up his college fellowship, which could not then be held by married men, and began tutoring and writing.[13]

An uncle, William Plumer, presented him with a living in Halesworth in Suffolk, and Whately moved there. His daughters were writer Jane Whately and missionary Mary Louisa Whately.[14] One of his nephews was Canon William Pope.[15]

Death

[edit]

Beginning in 1856, Whately began experiencing symptoms of decline, including paralysis of his left side, but he continued his public duties.[17]

In the summer of 1863, Whately was prostrated by an ulcer in his leg; after several months of acute suffering, he died on 8 October 1863.[7]

Works

[edit]Whately was a prolific writer, a successful expositor and Protestant apologist in works that ran to many editions and translations. His Elements of Logic (1826) was drawn from an article "Logic" in the Encyclopædia Metropolitana.[18] The companion article on "Rhetoric" provided Elements of Rhetoric (1828).[7] In these two works Whately introduced erotetic logic.[19]

In 1825 Whately published a series of Essays on Some of the Peculiarities of the Christian Religion, followed in 1828 by a second series On Some of the Difficulties in the Writings of St Paul, and in 1830 by a third On the Errors of Romanism Traced to Their Origin in Human Nature. In 1837 he wrote his handbook of Christian Evidences, which was translated during his lifetime into more than a dozen languages.[7] In the Irish context, the Christian Evidences was adapted to a form acceptable to Catholic beliefs, with the help of James Carlile.[20]

Selective listing

[edit]Whately's works included:[7]

- 1819 Historic Doubts relative to Napoleon Buonaparte, a jeu d'ésprit directed against excessive scepticism as applied to the Gospel history.[3]

- 1822 On the Use and Abuse of Party Spirit in Matters of Religion (Bampton Lectures)

- 1825 Essays on Some of the Peculiarities of the Christian Religion

- 1826 Elements of Logic

- 1828 Elements of Rhetoric

- 1828 On Some of the Difficulties in the Writings of St Paul

- 1830 On the Errors of Romanism Traced to Their Origin in Human Nature

- 1831 Introductory Lectures on Political Economy, 1st ed. (London: B. Fellowes). Eight lectures.

- 1832 Introductory Lectures on Political Economy, 2nd ed. (London: B. Fellowes). Nine lectures and appendix.

- 1832 A View of the Scripture Revelations Concerning a Future State, lectures advancing belief in Christian mortalism.

- 1832 Thoughts on the Sabbath

- 1836 Charges and Tracts

- 1839 Essays on Some of the Dangers to Christian Faith

- 1841 The Kingdom of Christ

- 1845 onwards "Easy Lessons": On Reasoning, On Morals, On Mind, and On the British Constitution

(Linked works are from Internet Archive)

Editor

[edit]- William Wake (1866) Treatises of Predestination[21]

- Francis Bacon (1858) Bacon's Essays with Annotations, See Essays (Francis Bacon).

- William Paley: (1837) [1796] A View of the Evidences of Christianity, in three parts

- William Paley: Moral Philosophy[7]

Character

[edit]Humphrey Lloyd told Caroline Fox that Whately's eccentric behaviour and body language was exacerbated in Dublin by a sycophantic circle of friends.[22] He was a great talker, a wit, and loved punning. In Oxford his white hat, rough white coat, and huge white dog earned for him the sobriquet of the White Bear, and he exhibited the exploits of his climbing dog in Christ Church Meadow.[7][23]

Views

[edit]A member of the loose group called the Oriel Noetics, Whately supported religious liberty, civil rights, and freedom of speech for dissenters, Roman Catholics, Jews, and even atheists. He took the line that the civil disabilities imposed on non-Anglicans made the state only nominally Christian, and supported disestablishment.[24] He was a follower of Edward Copleston, regarded as the founder of the Noetics taken as apologists for the orthodoxy of the Church of England.[3]

A devout Christian, Whately took a practical view of Christianity. He disagreed with the Evangelical party and generally favoured a more intellectual approach to religion. He also disagreed with the later Tractarian emphasis on ritual and church authority.[7] Instead, he emphasised careful reading and understanding of the Bible.[citation needed]

His cardinal principle was that of Chillingworth —‘the Bible, and the Bible alone, is the religion of protestants;’ and his exegesis was directed to determine the general tenor of the scriptures to the exclusion of dogmas based on isolated texts. There is no reason to question his reception of the central doctrines of the faith, though he shrank from theorising or even attempting to formulate them with precision. On election he held, broadly speaking, the Arminian view, and his antipathy to Calvinism was intense. He dwelt more on the life than on the death of Christ, the necessity of which he denied.[25]

Whately took a view of political economy as an essentially logical subject. It proved influential in Oxford. The Noetics were reformers but largely centrist in politics, rather than strong Whigs or Tories.[26] One of Whately's initial acts on going to Dublin was to endow a chair of political economy in Trinity College. Its first holder was Mountifort Longfield.[27] Later, in 1846, he founded the Dublin Statistical Society with William Neilson Hancock.[17]

Whately's view of political economy, and that common to the early holders of the Trinity college professorship, addressed it as a type of natural theology.[28] He belonged to the group of supporters of Thomas Malthus that included Thomas Chalmers, some others of the Noetics, Richard Jones and William Whewell from Cambridge.[29]

He saw no inconsistency between science and Christian belief, which differed from the view of other Christian critics of Malthus.[30] He differed also from Jones and Whewell, expressing the view that the inductive method was of less use for political economy than the deductive method, properly applied.[31]

In periodicals, Whately addressed other public questions, including the topic of transportation and the "secondary punishments" on those who had been transported; his pamphlet on this topic influenced the politicians Lord John Russell and Henry George Grey.[32]

Legacy

[edit]Whately was an important figure in the revival of Aristotelian logic in the early nineteenth century. The Elements of Logic gave an impetus to the study of logic in Britain,[7] and in the United States of America, logician Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) wrote that his lifelong fascination with logic began when he read Whately's Elements as a 12-year-old boy.[33]

Whately's view of rhetoric as essentially a method for persuasion became an orthodoxy, challenged in mid-century by Henry Noble Day.[34] Elements of Rhetoric is still cited, for thought about presumption, burden of proof, and testimony.[35][36]

Irish historian William Edward Hartpole Lecky thought Whately’s importance and influence greater than his later historical repute would indicate, and that Whately’s unsystematic, aphoristic style of writing might explain history’s relative forgetfulness of him:

He had a singular felicity of illustration, and especially of metaphor, and a rare power of throwing his thoughts into terse and pithy sentences; but his many books, though full of original thinking and in a high degree suggestive to other writers, had always a certain fragmentary and occasional character, which prevented them from taking a place in standard literature. He was conscious of it himself, and was accustomed to say that it was the mission of his life to make up cartridges for others to fire.[37]

In 1864, Jane Whately, his daughter, published Miscellaneous Remains from his commonplace book and in 1866 his Life and Correspondence in two volumes. The Anecdotal Memoirs of Archbishop Whately, by William John Fitzpatrick, was published in 1864.[7]

Notes and references

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Gary L. Colledge (1 June 2012). God and Charles Dickens: Recovering the Christian Voice of a Classic Author. Baker Books. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-4412-3778-1.

- ^ John Cornwell (15 September 2011). Newman's Unquiet Grave: The Reluctant Saint. A&C Black. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4411-7323-2.

- ^ a b c d e Brent, Richard. "Whately, Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29176. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Deane, Phyllis. "Senior, Nassau William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25090. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Stefan Collini; Richard Whatmore; Brian Young (22 May 2000). Economy, Polity, and Society: British Intellectual History 1750-1950. Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-521-63978-1.

- ^ "Life of Edward Bouverie Pusey by Henry Parry Liddon, D.D. London: Longmans, 1894 volume one Chapter X". Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ David de Giustino, "Finding an Archbishop: The Whigs and Richard Whately in 1831", Church History, Vol. 64, No. 2 (June., 1995), pp. 218–236. Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the American Society of Church History.

- ^ Stefan Collini; Richard Whatmore; Brian Young (22 May 2000). Economy, Polity, and Society: British Intellectual History 1750-1950. Cambridge University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-521-63978-1.

- ^ Larkin, Emmet. "Crolly, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17528. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Blain, Michael (2007). "Reverend" (PDF). The Canterbury Association (1848–1852): A Study of Its Members' Connections. p. 87. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter W" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ The London Quarterly Review. Epworth Press. 1867. p. 477.

- ^ Richard Whately; Elizabeth Jane Whately (1866). Life and Correspondence of Richard Whately, D.D.: Late Archbishop of Dublin. Longmans, Green. p. 44.

- ^ Gordon-Gorman, William James (1910). Converts to Rome : a biographical list of the more notable converts to the Catholic Church in the United Kingdom during the last sixty years. London: Sands. pp. 220, 221/242–243. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

Reverends William and John, both sons of Rev. F.S.W. Pope, were nephews of Richard Whately, Bishop of Dublin

- ^ Casey, Christine (2005). The Buildings of Ireland: Dublin. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 621. ISBN 978-0-300-10923-8.

- ^ a b Webb, Alfred (1878). . A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M. H. Gill & son.

- ^ Whately, Richard, Elements of Logic, p.vii, Longman, Greens and Co. (9th Edition, London, 1875).

- ^ Mary Prior and Arthur Prior, "Erotetic Logic", The Philosophical Review 64(1) (1955): pp. 43–59.

- ^ Donald H. Akenson (1985). Being Had: Historians, Evidence, and the Irish in North America. P. D. Meany. pp. 183–4. ISBN 978-0-88835-014-5.

- ^ The Living Age. Littell, Son and Company. 1866. p. 388.

- ^ Caroline Fox (1972). The Journals of Caroline Fox 1835-1871: A Selection. Elek Books. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-236-15447-0.

- ^ David de Giustino, Finding an Archbishop: The Whigs and Richard Whately in 1831, Church History Vol. 64, No. 2 (Jun., 1995), pp. 218–236. Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the American Society of Church History. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3167906.

- ^ Marilyn D. Button; Jessica A. Sheetz-Nguyen (4 November 2013). Victorians and the Case for Charity: Essays on Responses to English Poverty by the State, the Church and the Literati. McFarland. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-7864-7032-7.

- ^ McMullen Rigg 1885.

- ^ Nigel F. B. Allington; Noel W. Thompson (2010). English, Irish and Subversives Among the Dismal Scientists. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-85724-061-3.

- ^ Lee, Sidney, ed. (1893). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 34. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Thomas Boylan; Renee Prendergast; John Turner (1 March 2013). A History of Irish Economic Thought. Chief Research Scientist John Turner. Routledge. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-136-93349-3.

- ^ Donald Winch (26 January 1996). Riches and Poverty: An Intellectual History of Political Economy in Britain, 1750–1834. Cambridge University Press. pp. 371–2. ISBN 978-0-521-55920-1.

- ^ Winch, Donald (2009). Wealth and Life: Essays on the Intellectual History of Political Economy in Britain, 1848–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780521715393.

- ^ James P. Henderson (1996). Early Mathematical Economics: William Whewell and the British Case. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8476-8201-0.

- ^ Norval Morris (1998). The Oxford History of the Prison: The Practice of Punishment in Western Society. Oxford University Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-19-511814-8.

- ^ Fisch, Max, "Introduction", W 1:xvii.

- ^ Robert Connors (5 June 1997). Composition-Rhetoric: Backgrounds, Theory, and Pedagogy. University of Pittsburgh Pre. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-8229-7182-5.

- ^ Nicholas Rescher (19 June 2006). Presumption and the Practices of Tentative Cognition. Cambridge University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-139-45718-7.

- ^ Robert Crookall (1 November 1987). Intimations of Immortality: Seeing that Leads to Believing. James Clarke & Co. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-0-227-67662-2.

- ^ William Edward Hartpole Lecky, “Formative Influences,” Historical and Political Essays, p.85, (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1910) (retrieved June 9, 2024).

Sources

[edit]- Rigg, James McMullen (1899). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 60. pp. 423–429.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Whately, Richard". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

[edit]A modern biography is Richard Whately: A Man for All Seasons by Craig Parton ISBN 1-896363-07-5. See also Donald Harman Akenson A Protestant in Purgatory: Richard Whately, Archbishop of Dublin (South Bend, Indiana 1981)

- Einhorn, Lois J. "Consistency in Richard Whately: The Scope of His Rhetoric." Philosophy & Rhetoric 14 (Spring 1981): 89–99.

- Einhorn, Lois J. "Richard Whately's Public Persuasion: The Relationship between His Rhetorical Theory and His Rhetorical Practice." Rhetorica 4 (Winter 1986): 47–65.

- Einhorn, Lois J. "Did Napoleon Live? Presumption and Burden of Proof in Richard Whately's Historic Doubts Relative to Napoleon Boneparte." Rhetoric Society Quarterly 16 (1986): 285–97.

- Giustino, David de. "Finding an archbishop: the Whigs and Richard Whately in 1831." Church History 64 (1995): 218–36.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Richard Whately: Religious Controversialist of the Nineteenth Century." Prose Studies: 1800–1900 2 (1979): 160–87.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Archbishop Whately: Human Nature and Christian Assistance." Church History 50.2 (1981): 166–189.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Richard Whately on the Nature of Human Knowledge in Relation to the Ideas of his Contemporaries." Journal of the History of Ideas 42.3 (1981): 439–455.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Richard Whately's Theory of Rhetoric." In Explorations in Rhetoric. ed. R. McKerrow. Glenview IL: Scott, Firesman, & Co., 1982.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Richard Whately and the Revival of Logic in Nineteenth-Century England." Rhetorica 5 (Spring 1987): 163–85.

- McKerrow, Ray E. "Whately's Philosophy of Language." The Southern Speech Communication Journal 53 (1988): 211–226.

- Poster, Carol. "Richard Whately and the Didactic Sermon." The History of the Sermon: The Nineteenth Century. Ed. Robert Ellison. Leiden: Brill, 2010: 59–113.

- Poster, Carol. "An Organon for Theology: Whately's Rhetoric and Logic in Religious Context". Rhetorica 24:1 (2006): 37–77.

- Sweet, William. "Paley, Whately, and 'enlightenment evidentialism'". International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 45 (1999):143-166.

External links

[edit]- 1787 births

- 1863 deaths

- 19th-century British economists

- 19th-century English Anglican priests

- Alumni of Oriel College, Oxford

- Anglican archbishops of Dublin

- Anglican philosophers

- Burials at St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin

- Drummond Professors of Political Economy

- English logicians

- English philosophers

- English rhetoricians

- Fellows of Oriel College, Oxford

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Members of the Canterbury Association

- Members of the Privy Council of Ireland

- Principals of St Alban Hall, Oxford

- Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland