1911 Revolution

| 1911 Revolution 辛亥革命 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the anti-Qing movements | |||||||

Nanjing Road in Shanghai after the Shanghai Uprising, hung with the Five Races Under One Union flags used by revolutionaries in Shanghai and Northern China | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| 1911 Revolution | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 辛亥革命 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Xinhai (stem-branch) revolution" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

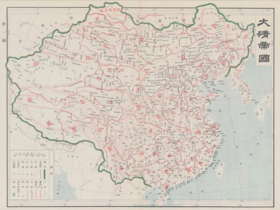

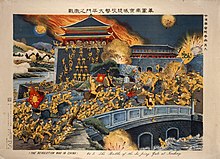

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a decade of agitation, revolts, and uprisings. Its success marked the collapse of the Chinese monarchy, the end of over two millennia of imperial rule in China and the 200-year reign of the Qing, and the beginning of China's early republican era.[2]

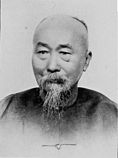

The Qing had struggled for a long time to reform the government and resist foreign aggression, but the program of reforms after 1900 was opposed by conservatives in the Qing court as too radical and by reformers as too slow. Several factions, including underground anti-Qing groups, revolutionaries in exile, reformers who wanted to save the monarchy by modernizing it, and activists across the country debated how or whether to overthrow the Qing dynasty. The flash-point came on 10 October 1911, with the Wuchang Uprising, an armed rebellion among members of the New Army. Similar revolts then broke out spontaneously around the country, and revolutionaries in all provinces of the country renounced the Qing dynasty. On 1 November 1911, the Qing court appointed Yuan Shikai (leader of the powerful Beiyang Army) as prime minister, and he began negotiations with the revolutionaries.

In Nanjing, revolutionary forces created a provisional coalition government. On 1 January 1912, the National Assembly declared the establishment of the Republic of China, with Sun Yat-sen, leader of the Tongmenghui (United League), as President of the Republic. A brief civil war between the North and the South ended in compromise. Sun would resign in favor of Yuan, who would become President of the new national government, if Yuan could secure the abdication of the Qing emperor. The edict of abdication of the six-year-old Xuantong Emperor, was promulgated on 12 February 1912. Yuan was sworn in as president on 10 March 1912.

In December 1915, Yuan restored the monarchy and proclaimed himself as the Hongxian Emperor, but the move was met with strong opposition from the population and the Army, leading to his abdication in March 1916 and the reinstatement of the Republic. Yuan's failure to consolidate a legitimate central government before his death in June 1916 led to decades of political division and warlordism, including an attempt at imperial restoration of the Qing dynasty.

The revolution is named Xinhai because it occurred in 1911, the year of the Xinhai (辛亥) stem-branch in the sexagenary cycle of the traditional Chinese calendar.[3] The governments of Taiwan and China both consider themselves the legitimate successors to the 1911 Revolution and honor the ideals of the revolution including nationalism, republicanism, modernization of China and national unity. 10 October is the National Day of the Republic of China on Taiwan, and the Anniversary of the 1911 Revolution in the PRC.

| Part of a series on |

| Political revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Three Principles of the People |

|---|

|

Background

After suffering its first defeat by the West in the First Opium War in 1842, a conservative court culture constrained efforts to reform and did not want to cede authority to local officials. Following defeat in the Second Opium War in 1860, the Qing began efforts to modernize by adopting Western technologies through the Self-Strengthening Movement. In the wars against the Taiping (1851–1864), Nian (1851–1868), Yunnan (1856–1873) and Dungan (1862–1877), the court came to rely on armies raised by local officials.[4] After a generation of relative success in importing Western naval and weapons technology, defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895 was all the more humiliating and convinced many of the need for institutional change.[5] The court established the New Army under Yuan Shikai and many concluded that Chinese society also needed to be modernized if technological and commercial advancements were to succeed.

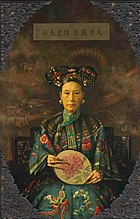

In 1898, the Guangxu Emperor turned to reformers like Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao who offered a program inspired in large part by the reforms in Japan. They proposed basic reform in education, military, and economy in the so-called Hundred Days' Reform.[5] The reform was abruptly canceled by a conservative coup led by Empress Dowager Cixi.[6] The Emperor was put under house arrest in June 1898, where he remained until his death in 1908.[4] Reformers Kang and Liang exiled themselves to avoid being executed. The Empress Dowager controlled policy until her death in 1908, with support from officials such as Yuan. Attacks on foreigners and Chinese Christians in the Boxer Rebellion, encouraged by the Empress Dowager, prompted another foreign invasion of Beijing in 1900.

After the Allies imposed a punitive settlement, the Qing court carried out basic fiscal and administrative reforms, including local and provincial elections. These moves did not secure trust or wide support among political activists. Many, like Zou Rong, felt strong anti-Manchu prejudice and blamed them for China's troubles. Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao formed the Emperor Protection Society in an attempt to restore the emperor,[4] but others, such as Sun Yat-sen organized revolutionary groups to overthrow the dynasty rather than reform it. They could operate only in secret societies and underground organizations, in foreign concessions, or exile overseas, but created a following among Chinese in North America and Southeast Asia, and within China, even in the new armies. The famine in 1906 and 1907 was also a major contributor to the revolution.[7] Following the death of the Guangxu Emperor and Cixi in 1908, the throne was inherited by the two-year-old Xuantong Emperor, with Prince Chun as a regent. The Prince continued the reform path of Cixi, but conservative Manchu elements in the court opposed it, causing further support for revolutionaries.

| History of the Republic of China |

|---|

|

|

|

Organization

Earliest groups

Many revolutionaries and groups wanted to overthrow the Qing government to re-establish the Han-led government. The earliest revolutionary organizations were founded outside of China, such as Yeung Ku-wan's Furen Literary Society, created in Hong Kong in 1890. There were 15 members, including Tse Tsan-tai, who did political satire such as "The Situation in the Far East", one of the first manhua, and who later became one of the core founders of the South China Morning Post.[8]

Sun Yat-sen's Revive China Society was established in Honolulu in 1894, with the main purpose of raising funds for revolutions.[9] The two organizations merged in 1894.[10]

Smaller groups

The Huaxinghui (China Revival Society) was founded in 1904 by notables like Huang Xing, Zhang Shizhao, Chen Tianhua, Sun Yat-sen, and Song Jiaoren, along with 100 others. Their motto was "Take one province by force, and inspire the other provinces to rise".[11]

The Guangfuhui (Restoration Society) was also founded in 1904, in Shanghai, by Cai Yuanpei. Other notable members include Zhang Binglin and Tao Chengzhang.[12] Despite professing the anti-Qing cause, the Guangfuhui was highly critical of Sun Yat-sen. One of the most famous female revolutionaries was Qiu Jin, who fought for women's rights and was also from Guangfuhui.[13]

Gelaohui (Elder Brother Society) was another group, with Zhu De, Wu Yuzhang, Liu Zhidan (劉志丹) and He Long. This revolutionary group would eventually develop a strong link with the later Communist Party.

Tongmenghui

Sun Yat-sen successfully united the Revive China Society, Huaxinghui and Guangfuhui in the summer of 1905, thereby establishing the unified Tongmenghui (United League) in August 1905 in Tokyo.[14] While it started in Tokyo, it had loose organizations distributed across and outside the country. Sun Yat-sen was the leader of this unified group. Other revolutionaries who worked with the Tongmenghui include Wang Jingwei and Hu Hanmin. When the Tongmenghui was established, more than 90% of the Tongmenghui members were between 17 and 26 years of age.[15] Some of the work in the era includes manhua publications such as the Journal of Current Pictorial.[16]

Later groups

In February 1906, Rizhihui (日知會) also had many revolutionaries, including Sun Wu (孫武), Zhang Nanxian (張難先), He Jiwei and Feng Mumin.[17][18] A nucleus of attendees at this conference evolved into the Tongmenghui's establishment in Hubei.

In July 1907, several members of Tongmenghui in Tokyo advocated a revolution in the area of the Yangtze. Liu Quiyi (劉揆一), Jiao Dafeng (焦達峰), Zhang Boxiang (張伯祥) and Sun Wu (孫武) established the Gongjinhui (共進會).[19][20] In January 1911, the revolutionary group Zhengwu Xueshe (振武學社) was renamed as Wenxueshe (Literary Society) (文學社).[21] Jiang Yiwu (蔣翊武) was chosen as the leader.[22] These two organizations would play a big role in the Wuchang Uprising.

Many young revolutionaries adopted the anarchist program. In Tokyo, Liu Shipei proposed to overthrow the Manchus and return to Chinese classical values. In Paris, well-connected young intellectuals, Li Shizhen, Wu Zhihui and Zhang Renjie, agreed with Sun's revolutionary program and joined the Tongmenghui, but argued that simply replacing one government with another would not be progress; fundamental cultural change, a revolution in family, gender and social values, would remove the need for government and coercion. Zhang Ji and Wang Jingwei were among the anarchists who defended assassination and terrorism as means to awaken the people to revolution, but others insisted that education was the only justifiable strategy. Important anarchists included Cai Yuanpei. Zhang Renjie gave Sun major financial help. Many of these anarchists would later assume high positions in the Kuomintang (KMT).[23]

Views

Many revolutionaries promoted anti-Qing/anti-Manchu sentiments and revived memories of conflict between the ethnic minority Manchu and the ethnic majority Han Chinese from the late Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Leading intellectuals were influenced by books that had survived from the final years of the Ming dynasty, the last dynasty of Han Chinese. In 1904, Sun Yat-sen announced that his organization's goal was "to expel the Tatar barbarians, to revive Zhonghua, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people." (驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權).[14] Many underground groups promoted the ideas of "Resist Qing and restore Ming" (反清復明) that had been around since the days of the Taiping Rebellion.[24] Others, such as Zhang Binglin, supported straight-up lines like "slay the Manchus" and concepts like "Anti-Manchuism" (興漢滅胡 or 排滿主義).[25]

Society and class

Many groups supported the 1911 Revolution, including students and intellectuals returning from abroad, as well as participants of revolutionary organizations, overseas Chinese, soldiers of the new army, local gentry, farmers, and others.

Overseas Chinese

Assistance from overseas Chinese was important in the 1911 Revolution. In 1894, the first year of the Revive China Society, the first meeting ever held by the group was held in the home of Ho Fon, an overseas Chinese who was the leader of the first Chinese Church of Christ.[26] Overseas Chinese supported and actively participated in funding revolutionary activities, especially the Southeast Asian Chinese of British Malaya. Many of these groups were reorganized by Sun, who was referred to as the "father of the Chinese revolution".[27]

Emerging intellectual class

The Qing government established new schools and encouraged students to study abroad as part of the Self-Strengthening movement. Many young people attended the new schools or went abroad to study in places like Japan.[28] A new progressive class of intellectuals emerged from those students, who contributed immensely to the 1911 Revolution. Besides Sun Yat-sen, key figures in the revolution, such as Huang Xing, Song Jiaoren, Hu Hanmin, Liao Zhongkai, Zhu Zhixin and Wang Jingwei, were all Chinese students in Japan. Some were young students like Zou Rong, known for writing Revolutionary Army, a book in which he talked about the extermination of the Manchus for the 260 years of oppression, sorrow, cruelty, and tyranny, and creating new revolutionary Han figures.[29]

Before 1908, revolutionaries focused on coordinating these organizations in preparation for uprisings they would launch; hence, these groups would provide most of the manpower needed for the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty. After the 1911 Revolution, Sun Yat-sen recalled the days of recruiting support for the revolution and said, "The literati were deeply into the search for honors and profits, so they were regarded as having only secondary importance. By contrast, organizations like Sanhehui were able to sow widely the ideas of resisting the Qing and restoring the Ming."[30]

Gentry and businessmen

The gentry's strength in local politics became apparent. From December 1908, the Qing government created some apparatus to allow the gentry and businessmen to participate in politics. These middle-class people were originally supporters of constitutionalism. However, they became disenchanted when the Qing government created a cabinet with Prince Qing as prime minister.[31] By early 1911, an experimental cabinet had thirteen members, nine of whom were Manchus selected from the imperial family.[32]

Foreign supporters

Besides Chinese and overseas Chinese, some supporters and participants of the 1911 Revolution were foreigners; among them, the Japanese were the most active group. Some Japanese even became members of Tongmenghui. Miyazaki Touten was the closest Japanese supporter; others included Heiyama Shu and Ryōhei Uchida. Homer Lea, an American, who became Sun Yat-sen's closest foreign advisor in 1910, supported Sun Yat-sen's military ambitions.[33] British soldier Rowland J. Mulkern also took part in the revolution.[34] Some foreigners, such as English explorer Arthur de Carle Sowerby, led expeditions to rescue foreign missionaries in 1911 and 1912.[35]

The far right-wing Japanese ultra-nationalist Black Dragon Society supported Sun Yat-sen's activities against the Manchus, believing that overthrowing the Qing would help the Japanese take over the Manchu homeland and that Han Chinese would not oppose the takeover. Toyama believed that the Japanese could easily take over Manchuria and that Sun Yat-sen and other anti-Qing revolutionaries would not resist and help the Japanese take over and enlarge the opium trade in China, while the Qing was trying to destroy the opium trade. The Japanese Black Dragons supported Sun Yat-sen and anti-Manchu revolutionaries until the Qing collapsed.[36] The far right-wing Japanese ultranationalist Gen'yōsha leader Tōyama Mitsuru supported anti-Manchu, anti-Qing revolutionary activities including the ones organized by Sun and supported Japanese taking over Manchuria. The anti-Qing Tongmenghui was founded and based in exile in Japan where many anti-Qing revolutionaries gathered.

The Japanese had been trying to unite anti-Manchu groups made out of Han people to take down the Qing. The Japanese were the ones who helped Sun Yat-sen unite all anti-Qing, anti-Manchu revolutionary groups together, and there were Japanese like Tōten Miyazaki inside of the anti-Manchu Tongmenghui revolutionary alliance. The Black Dragon Society hosted the Tongmenghui in its first meeting.[37] The Black Dragon Society had very intimate, long term and influential relations with Sun Yat-sen who sometimes passed himself off as Japanese.[38][39][40] According to an American military historian, Japanese military officers were part of the Black Dragon Society. The Yakuza and Black Dragon Society helped arrange in Tokyo for Sun Yat-sen to hold the first Kuomintang meetings, and were hoping to flood China with opium and overthrow the Qing and deceive the Chinese into overthrowing the Qing to Japan's benefit. After the revolution was successful, the Japanese Black Dragons started infiltrating China and spreading opium. The Black Dragons pushed for the takeover of Manchuria by Japan in 1932.[41] Sun Yat-sen was married to a Japanese woman, Kaoru Otsuki.

Soldiers of the New Armies

The New Army was formed in 1901 after the defeat of the Qing in the First Sino-Japanese War. They were launched by a decree from eight provinces. New Army troops were by far the best trained and equipped. Recruits were of a higher quality than the old army and received regular promotions.[28] Beginning in 1908, the revolutionaries began to shift their call to the new armies. Sun Yat-sen and the revolutionaries infiltrated the New Army.[42]

Prelude

The central foci of the uprisings were mostly connected with the Tongmenghui and Sun Yat-sen, including subgroups. Some uprisings involved groups that never merged with the Tongmenghui. Sun Yat-sen may have participated in 8–10 uprisings; all uprisings failed before the Wuchang Uprising.

First Guangzhou Uprising

In the spring of 1895, the Revive China Society, based in Hong Kong, planned the First Guangzhou Uprising. Lu Haodong was tasked with designing the revolutionaries' Blue Sky with a White Sun flag.[27] On 26 October 1895, Yeung Ku-wan and Sun Yat-sen led Zheng Shiliang and Lu Haodong to Guangzhou, preparing to capture Guangzhou in one strike. However, the details of their plans were leaked to the Qing government. The government began to arrest revolutionaries, including Lu Haodong, who was later executed.[43] The First Guangzhou Uprising was a failure. Under pressure from the Qing government, the government of Hong Kong banned the two men from the territory for five years. Sun Yat-sen went into exile, promoting the Chinese revolution and raising funds in Japan, the United States, Canada, and Britain. In 1901, following the Huizhou Uprising, Yeung Ku-wan was assassinated by Qing agents in Hong Kong. After his death, his family protected his identity by not putting his name on his tomb, just the number "6348".[44]

Independence Army Uprising

In 1900, after the Boxer Rebellion started, Tang Caichang (唐才常) and Tan Sitong of the previous Foot Emancipation Society organized the Independence Army. The Independence Army Uprising (自立軍起義) was planned to occur on 23 August 1900. Their goal was to overthrow Empress Dowager Cixi to establish a constitutional monarchy under the Guangxu Emperor. Their plot was discovered by the governors-general of Hunan and Hubei. About twenty conspirators were arrested and executed.[45]

Huizhou Uprising

On 8 October 1900, Sun Yat-sen ordered the launch of the Huizhou Uprising (惠州起義).[46] The revolutionary army was led by Zheng Shiliang and initially included 20,000 men, who fought for half a month. However, after Japanese prime minister Hirobumi Ito prohibited Sun Yat-sen from carrying out revolutionary activities on Taiwan, Zheng Shiliang had no choice but to order the army to disperse. Accordingly, this uprising also failed. British soldier Rowland J. Mulkern participated in this uprising.[34]

Great Ming Uprising

A very short uprising occurred from 25 to 28 January 1903, to establish a "Great Ming Heavenly Kingdom" (大明順天國).[47] This involved Tse Tsan-tai, Li Jitang (李紀堂), Liang Muguang (梁慕光) and Hong Quanfu (洪全福), who formerly took part in the Jintian uprising during the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom era.[48]

Ping-liu-li Uprising

Ma Fuyi (馬福益) and Huaxinghui was involved in an uprising in the three areas of Pingxiang, Liuyang and Liling, called "Ping-liu-li Uprising", (萍瀏醴起義) in 1905. The uprising recruited miners as early as 1903 to rise against the Qing ruling class. After the uprising failed, Ma Fuyi was executed.[49]

Beijing assassination attempt

Wu Yue (吳樾) of the Guangfuhui carried out an assassination attempt at the Beijing Zhengyangmen East Railway station (正陽門車站) in an attack on five Qing officials on 24 September 1905.[13][50]

Huanggang Uprising, Chaozhou

The Huanggang Uprising (黃岡起義) was launched on 22 May 1907, in Chaozhou.[51] The revolutionary party, along with Xu Xueqiu (許雪秋), Chen Yongpo (陳湧波) and Yu Tongshi (余通實), launched the uprising and captured Huanggang city.[51] After the uprising began, the Qing government quickly and forcefully suppressed it. Around 200 revolutionaries were killed.[52]

Huizhou Qinühu Uprising, Huizhou

In the same year, Sun Yat-sen sent more revolutionaries to Huizhou to launch the "Huizhou Qinühu Uprising" (惠州七女湖起義).[53] On 2 June, Deng Zhiyu (鄧子瑜) and Chen Chuan (陳純) gathered some followers, and together they seized Qing arms in the lake, 20 km (12 mi) from Huizhou.[54] They killed several Qing soldiers and attacked Taiwei (泰尾) on 5 June.[54] The Qing army fled in disorder, and the revolutionaries exploited the opportunity, capturing several towns. They defeated the Qing army once again in Bazhiyie. Many organizations voiced their support after the uprising, and the number of revolutionary forces increased to two hundred men at its height. The uprising, however, ultimately failed.

Anqing Uprising

On 6 July 1907, Xu Xilin of Guangfuhui led an uprising in Anqing, Anhui, which became known as the Anqing Uprising (安慶起義).[21] Xu Xilin at the time was the police commissioner as well as the supervisor of the police academy. He led an uprising that aimed to assassinate the provincial governor of Anhui, En Ming (恩銘).[55] They were defeated after four hours of fighting. Xu was captured, and En Ming's bodyguards cut out his heart and liver and ate them.[55] His cousin Qiu Jin was executed a few days later.[55]

Qinzhou Uprising

From August to September 1907, the Qinzhou Uprising occurred (欽州防城起義),[56] to protest against heavy taxation from the government. Sun Yat-sen sent Wang Heshun (王和順) there to assist the revolutionary army and captured the county in September.[57] After that, they attempted to besiege and capture Qinzhou but were unsuccessful. They eventually retreated to the area of Shiwandashan, while Wang Heshun returned to Vietnam.

Zhennanguan Uprising

On 1 December 1907, the Zhennanguan Uprising (鎮南關起事) took place at Zhennanguan along the Chinese-Vietnamese border. Sun Yat-sen sent Huang Mintang (黃明堂) to monitor the pass, which was guarded by a fort.[57] With the assistance of supporters among the fort's defenders, the revolutionaries captured the cannon tower in Zhennanguan. Sun Yat-sen, Huang Xing and Hu Hanmin personally went to the tower to command the battle.[58] The Qing government sent troops led by Long Jiguang and Lu Rongting to counterattack, and the revolutionaries were forced to retreat into the mountainous areas. After this uprising's failure, Sun was forced to move to Singapore due to anti-Sun sentiments within the revolutionary groups.[59] He would not return to the mainland until after the Wuchang Uprising.

Qin-Lian Uprising, Guangdong

On 27 March 1908, Huang Xing launched a raid, later known as the Qin-lian Uprising (欽廉上思起義), from a base in Vietnam and attacked the cities of Qinzhou and Lianzhou in Guangdong. The struggle continued for fourteen days but was forced to stop after the revolutionaries ran out of supplies.[60]

Hekou Uprising, Yunnan

In April 1908, another uprising was launched in Yunnan, Hekou, called the Hekou Uprising (雲南河口起義). Huang Mingtang (黃明堂) led two hundred men from Vietnam and attacked Hekou on 30 April. Other participating revolutionaries included Wang Heshun (王和順) and Guan Renfu (關仁甫). They were outnumbered and defeated by government troops, however, and the uprising failed.[61]

Mapaoying Uprising, Anhui

On 19 November 1908, the Mapaoying Uprising (馬炮營起義) was launched by revolutionary group Yuewanghui (岳王會) member Xiong Chenggei (熊成基) in Anhui.[62] Yuewanghui, at this time, was a subset of Tongmenghui. This uprising also failed.

Guangzhou

In February 1910, the Gengxu New Army Uprising (庚戌新軍起義), also known as the Guangzhou New Army Uprising (廣州新軍起義), took place.[63] This involved a conflict between the citizens and local police against the New Army. After revolutionary leader Ni Yingdian was killed by Qing forces, the remaining revolutionaries were quickly defeated, causing the uprising to fail.

On 27 April 1911, an uprising occurred in Guangzhou, known as the Second Guangzhou Uprising (辛亥廣州起義) or Yellow Flower Mound Revolt (黃花岡之役). It ended in disaster, as 86 bodies were found (only 72 could be identified).[64] The 72 revolutionaries were remembered as martyrs.[64] Revolutionary Lin Juemin was one of the 72. On the eve of battle, he wrote "A Letter to My Wife" (與妻訣別書), later to be considered a masterpiece in Chinese literature.[65]

Wuchang Uprising

The Literary Society (文學社) and the Progressive Association (共進會) were revolutionary organizations involved in the uprising that mainly began with a Railway Protection Movement protest.[20] In the late summer, some Hubei New Army units were ordered to neighboring Sichuan to quell the Railway Protection Movement, a mass protest against the Qing government's seizure and handover of local railway development ventures to foreign powers.[66][better source needed] Banner officers like Duanfang, the railroad superintendent,[67] and Zhao Erfeng led the New Army against the Railway Protection Movement.

The New Army units of Hubei had originally been the Hubei Army, which had been trained by Qing official Zhang Zhidong.[2] On 24 September, the Literary Society and Progressive Association convened a conference in Wuchang, along with sixty representatives from local New Army units. During the conference, they established a headquarters for the uprising. The leaders of the two organizations, Jiang Yiwu (蔣翊武) and Sun Wu (孫武), were elected as commander and chief of staff. Initially, the date of the uprising was to be 6 October 1911.[68] It was postponed to a later date due to insufficient preparations.

Revolutionaries intent on overthrowing the Qing dynasty had built bombs, and on 9 October, one accidentally exploded.[68] Sun Yat-sen himself had no direct part in the uprising and was traveling in the United States at the time to recruit more support from among overseas Chinese. The Qing Viceroy of Huguang, Rui Cheng (瑞澂), tried to track down and arrest the revolutionaries.[69] Squad leader Xiong Bingkun (熊秉坤) and others decided not to delay the uprising any longer and launched the revolt on 10 October 1911, at 7:00 p.m.[69] The revolt was a success; the entire city of Wuchang was captured by the revolutionaries on the morning of 11 October. That evening, they established a tactical headquarters and announced the establishment of the "Military Government of Hubei of Republic of China".[69] The conference chose Li Yuanhong as the governor of the temporary government.[69] Qing officers like the bannermen Duanfang and Zhao Erfeng were killed by the revolutionary forces.

Revolutionaries killed a German arms dealer in Hankou as he was delivering arms to the Qing.[70] Revolutionaries killed 2 Germans and wounded 2 other Germans at the battle of Hanyang, including a former colonel.[71]

Provincial uprisings

After the success of the Wuchang Uprising, many other protests occurred throughout the country for various reasons. Some uprisings declared restoration (光復) of the Han Chinese rule. Other uprisings were a step toward independence, and some were protests or rebellions against the local authorities.[citation needed] Regardless of the reason for the uprising the outcome was that all provinces in the country renounced the Qing dynasty and joined the ROC.

Changsha

On 22 October 1911, the Hunan Tongmenghui were led by Jiao Dafeng (焦達嶧) and Chen Zuoxin (陳作新).[72] They headed an armed group, consisting partly of revolutionaries from Hongjiang and partly of defecting New Army units, in a campaign to extend the uprising into Changsha.[72] They captured the city and killed the local Imperial general. Then they announced the establishment of the Hunan Military Government of the Republic of China and announced their opposition to the Qing Empire.[72]

Shaanxi

On the same day, Shaanxi's Tongmenghui, led by Jing Dingcheng (景定成) and Qian Ding (錢鼎) as well as Jing Wumu (井勿幕) and others including Gelaohui, launched an uprising and captured Xi'an after two days of struggle.[73] The Hui Muslim community was divided in its support for the revolution. The Hui Muslims of Shaanxi supported the revolutionaries, while the Hui Muslims of Gansu supported the Qing. The native Hui of Xi'an joined the Han Chinese revolutionaries in slaughtering the Manchus.[74][75] The native Hui Muslims of Gansu province led by general Ma Anliang led more than twenty battalions of Hui troops to defend the Qing imperials and attacked Shaanxi, held by revolutionary Zhang Fenghui (張鳳翽).[76] The attack was successful, and after news arrived that Puyi was about to abdicate, Ma agreed to join the new Republic.[76] The revolutionaries established the "Qinlong Fuhan Military Government" and elected Zhang Fenghui, a member of the Yuanrizhi Society (原日知會), as new governor.[73] After the Xi'an Manchu quarter fell on 24 October, Xinhai forces killed all the Manchus in the city, about 20,000 Manchus were killed in the massacre. Many of its Manchu defenders committed suicide, including Qing general Wenrui (文瑞), who threw himself down a well. Only some wealthy Manchus who were ransomed and Manchu females survived. Wealthy Han Chinese seized Manchu girls to become their slaves and poor Han Chinese troops seized young Manchu women to be their wives.[77] Young Manchu girls were also seized by Hui Muslims of Xi'an during the massacre and brought up as Muslims.[78]

Hui General Ma Anliang abandoned the Qing cause upon the Qing abdication in the Xinhai Revolution while the Manchu governor general Shengyun was enraged at the revolution.[79][80]

Pro-revolution Hui Muslims like Shaanxi Governor Ma Yugui and Beijing Imam Wang Kuan persuaded Qing Hui general Ma Anliang to stop fighting, telling him as Muslims not to kill each other for the sake of the Qing monarchists and side with the republican revolutionaries instead. Ma Anliang then agreed to abandon the Qing under the combination of Yuan Shikai's actions and these messages from other Hui.[81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90]

A year before the massacre of Manchus in October 1911, an oath against Manchus was sworn at the Great Goose Pagoda in Xi'an by the Gelaohui in 1911.[91][92][93] Manchu banner garrisons were slaughtered in Nanjing, Zhenjiang, Taiyuan, Xi'an and Wuchang[94][95][96][97][98] The Manchu quarter was located in the north eastern part of Xi'an and walled off while the Hui Muslim quarter was located in the northwestern part of Xi'an but did not have walls separating it from the Han parts. Southern Xi'an was entirely Han.[99][100][101][102][better source needed] Xi'an had the biggest Manchu banner garrison quarter by area before its destruction.[103]

The revolutionaries were led by students of the military academy who overcame the guards at the gates of Xi'an and shut them, secured the arsenal and slaughtering all Manchus at their temple and then storming and slaughtering the Manchus in the Manchu banner quarter of the city. The Manchu quarter was set on fire and many Manchus were burned alive. Manchu men, women and girls were slaughtered for three days and then after that, only Manchu women and girls were spared while Manchu men and boys continued to be slaughtered. Many Manchus committed suicide by overdosing on opium and throwing themselves into wells. The revolutionaries were helped by the fact that Manchus stored gunpowder in their houses so they exploded when set on fire, killing the Manchus inside. 10,000 to 20,000 Manchus were slaughtered.[104]

Ma Anliang was ordered to attack the revolutionaries in Shaanxi by the baoyi bondservant Chang Geng and Manchu Shengyun.[105][106]

Eastern soldiers of the new republic were mobilized by Yuan Shikai when the attack against Shaanxi began by Ma Anliang, but news of the abdication of the Qing emperor reached Ma Anliang before he attacked Xi'an, so Ma Anliang ended all military operations and changed his allegiance to the Republic of China. All pro-Qing military activity in the northwest was put to an end by this.[107]

Yuan Shikai managed to induce Ma Anliang to not attack Shaanxi after the Gelaohui took over the province and accept the Republic of China under his presidency in 1912. During the National Protection war in 1916 between republicans and Yuan Shikai's monarchy, Ma Anliang readied his soldiers and informed the republicans that he and the Muslims would stick to Yuan Shikai until the end.[108] Yuan Shikai ordered Ma Anliang to block Bai Lang (White Wolf) from going into Sichuan and Gansu by blocking Hanzhong and Fengxiangfu.[109]

The Protestant Shensi mission operated a hospital in Xian.[110] Some American missionaries were reported killed in Xi'an.[111] A report claimed Manchus massacred missionaries in the suburbs of Xi'an.[112] Missionaries were reported killed in Xi'an and Taiyuan.[113] Shaanxi joined the revolution on October 24.[114] Sheng Yun was governor of Shaanxi in 1905.[115][116][117]

Some Gansu Hui led by Ma Fuxiang joined the republicans. Gansu Hui general Ma Fuxiang did not participate with Ma Anliang in the battles with Shaanxi revolutionaries and refused to join the Qing Manchu Shengyun and Changgeng in their attempts to defend the Qing before the Qing abdication, instead the independence of Gansu from Qing control was jointly declared by non-Muslim gentry with Hui Muslim Ma Fuxiang.[118]

Jiujiang

On 23 October, Lin Sen, Jiang Qun (蔣群), Cai Hui (蔡蕙) and other members of the Tongmenghui in the province of Jiangxi plotted a revolt of New Army units.[72][120] A Qing naval fleet also revolted against the state, which solidified victory in the Wuchang Uprising.[121] After they achieved victory, they announced their independence. The Jiujiang Military Government was then established.[120]

Shanxi

On 29 October, Yan Xishan of the New Army led an uprising in Taiyuan, the capital city of the province of Shanxi.[120][122] The rebels in Taiyuan bombarded the streets where Banner people resided and killed all the Manchu.[123] They managed to kill the Qing Governor of Shanxi, Lu Zhongqi (陸鍾琦).[124] They then announced the establishment of Shanxi Military Government with Yan Xishan as the military governor.[73]

Kunming

On 30 October, Li Genyuan (李根源) of the Tongmenghui in Yunnan joined with Cai E, Luo Peijin (羅佩金), Tang Jiyao, and other officers of the New Army to launch the Double Ninth Uprising (重九起義).[125] They captured Kunming the next day and established the Yunnan Military Government, electing Cai E as the military governor.[120]

Nanchang

On 31 October, the Nanchang branch of the Tongmenghui led New Army units in a successful uprising. They established the Jiangxi Military Government.[72] Li Liejun was elected as the military governor.[120] Li declared Jiangxi as independent and launched an expedition against Qing official Yuan Shikai.[65]

Shanghai

On 3 November, Shanghai's Tongmenghui, Guangfuhui and merchants led by Chen Qimei, Li Pingsu (李平書), Zhang Chengyou (張承槱), Li Yingshi (李英石), Li Xiehe (李燮和) and Song Jiaoren organized an armed rebellion in Shanghai.[120] They received support from local police officers.[120] The rebels captured the Jiangnan Workshop on the 4th and captured Shanghai soon after. On 8 November, they established the Shanghai Military Government and elected Chen Qimei as the military governor.[120] He would eventually become one of the founders of the four big families of the Republic of China, along with some of the most well-known families of the era.[126]

Guizhou

On 4 November, Zhang Bailin (張百麟) of the revolutionary party in Guizhou led an uprising along with New Army units and students from the military academy. They immediately captured Guiyang and established the Great Han Guizhou Military Government, electing Yang Jincheng (楊藎誠) and Zhao Dequan (趙德全) as the chief and vice governor respectively.[127]

Zhejiang

Also on 4 November, revolutionaries in Zhejiang urged the New Army units in Hangzhou to launch an uprising.[120] Zhu Rui (朱瑞), Wu Siyu (吳思豫), Lu Gongwang (吕公望) and others of the New Army captured the military supplies workshop.[120] Other units, led by Chiang Kai-shek and Yin Zhirei (尹銳志), captured most of the government offices.[120] Eventually, Hangzhou was under the control of the revolutionaries, and the constitutionalist Tang Shouqian (湯壽潛) was elected as the military governor.[120]

Jiangsu

On 5 November, Jiangsu constitutionalists and gentry urged Qing governor Cheng Dequan (程德全) to announce independence and established the Jiangsu Revolutionary Military Government with Cheng himself as the governor.[120][128] Unlike some other cities, anti-Manchu violence began after the restoration on 7 November in Zhenjiang. Qing general Zaimu (載穆) agreed to surrender, but because of a misunderstanding, the revolutionaries were unaware that their safety was guaranteed. The Manchu quarters were ransacked, and an unknown number of Manchus were killed. Zaimu, feeling betrayed, committed suicide.[129] This is regarded as the Zhenjiang Uprising (鎮江起義).[130][131]

Anhui

Members of Anhui's Tongmenghui also launched an uprising on that day and laid siege to the provincial capital. The constitutionalists persuaded Zhu Jiabao, the Qing governor of Anhui, to announce independence.[132]

Guangxi

On 7 November, the Guangxi politics department decided to secede from the Qing government, announcing Guangxi's independence. Qing Governor Shen Bingkun (沈秉堃) was allowed to remain governor, but Lu Rongting would soon become the new governor.[57] Lu Rongting would later rise to prominence during the Warlord Era, and his bandits controlled Guangxi for more than a decade.[133] Under leadership of Huang Shaohong, the Muslim law student Bai Chongxi was enlisted into a Dare to Die unit to fight as a revolutionary.[134]

Fujian

In November, members of Fujian's branch of the Tongmenghui, along with Sun Daoren (孫道仁) of the New Army, launched an uprising against the Qing army.[135][136] The Qing viceroy, Song Shou (松壽), committed suicide.[137] On 11 November, the entire Fujian province declared independence.[135] The Fujian Military Government was established, and Sun Daoren was elected as the military governor.[135]

Guangdong

Near the end of October, Chen Jiongming, Deng Keng (鄧鏗), Peng Reihai (彭瑞海) and other members of Guangdong's Tongmenghui organized local militias to launch the uprising in Huazhou, Nanhai, Sunde and Sanshui in Guangdong Province.[73][138] On 8 November, after being persuaded by Hu Hanmin, General Li Zhun (李準) and Long Jiguang (龍濟光) of the Guangdong Navy agreed to support the revolution.[73] The Qing viceroy of Liangguang, Zhang Mingqi (張鳴岐), was forced to discuss with local representatives a proposal for Guangdong's independence.[73] They decided to announce it the next day. Chen Jiongming then captured Huizhou. On 9 November, Guangdong announced its independence and established a military government.[139] They elected Hu Hanmin and Chen Jiongming as Chief and Vice-Governor.[140] Qiu Fengjia is known to have helped make the independence declaration more peaceful.[139] It was unknown at the time if representatives from the European colonies of Hong Kong and Macau would be ceded to the new government.[clarification needed]

Shandong

On 13 November, after being persuaded by revolutionary Ding Weifen and several other officers of the New Army, the Qing governor of Shandong, Sun Baoqi, agreed to secede from the Qing government and announced Shandong's independence.[73]

Ningxia

On 17 November, Ningxia Tongmenghui launched the Ningxia Uprising (寧夏會黨起義). The revolutionaries sent Yu Youren to Zhangjiachuan to meet Dungan Sufi master Ma Yuanzhang to persuade him not to support the Qing. However, Ma did not want to endanger his relationship with the Qings. He sent the eastern Gansu Muslim militia under the command of one of his sons to help Ma Qi fight the Ningxia Gelaohui.[141][142] Ma Anliang, Changgeng and Shengyun failed to capture Shaanxi from the revolutionaries. In Ningxia, Qing forces were attacked by both Hui Muslim Gelaohui and Han Gelaohui members, while Hui general Ma Qi and Ma Yuanzhang were in the Qing forces fighting against them but Ma Yuanzhang defected to the republicans after Ma Anliang gave up on the Qing.[143] However, the Ningxia Revolutionary Military Government was established on 23 November.[73] Some revolutionaries involved included Huang Yue (黃鉞) and Xiang Shen (向燊), who gathered New Army forces at Qinzhou (秦州).[144][145]

Sichuan

On 21 November, Guang'an organized the Great Han Shu Northern Military Government.[73][146]

On 22 November, Chengdu and Sichuan declared independence. By the 27th, the Great Han Sichuan Military Government was established, headed by revolutionary Pu Dianzun (蒲殿俊).[73] Qing official Duanfang would also be killed.[73]

Nanjing

On 8 November, supported by the Tongmenghui, Xu Shaozhen (徐紹楨) of the New Army announced an uprising in Molin Pass (秣陵關), 30 km (19 mi) away from Nanjing. Xu Shaozhen, Chen Qimei and other generals decided to form a united army under Xu to strike Nanjing together. On 11 November, the united army headquarters was established in Zhenjiang. Between 24 November and 1 December, under the command of Xu Shaozhen, the united army captured Wulongshan (烏龍山), Mufushan (幕府山)), Yuhuatai (雨花臺)), Tianbao (天保城)) among other Qing army strongholds. On 2 December, Nanjing was captured by the revolutionaries after the Battle of Nanjing, 1911.[73] On 3 December, revolutionary Su Liangbi led troops in a massacre of a large number of Manchus. Shortly afterward he was arrested and his troops disbanded.[147]

Dihua and Yili Uprising

In Xinjiang on 28 December, Liu Xianzun (劉先俊) and revolutionaries started the Dihua Uprising (迪化起義).[148] This was led by more than 100 members of Gelaohui.[149] This uprising failed. On 7 January 1912, the Yili Uprising (伊犁起義) with Feng Temin began.[148][149] Qing governor Yuan Dahua (袁大化) fled and submitted his resignation to Yang Zengxin, because he could not handle fighting the revolutionaries.[150]

On 8 January, a new Yili government was established for the revolutionaries. Today some Chinese historians believe this contributed to the Qing dynasty fall, because this prevented the Qing dynasty's plan to flee to the western country.[151][149] The revolutionaries would be defeated at Jinghe in January and February,[150][152] eventually, because of the abdication to come, Yuan Shikai recognized Yang Zengxin's rule, appointed him Governor of Xinjiang and had the province join the Republic.[150] Eleven more former Qing officials would be assassinated in Zhenxi, Karashahr, Aksu, Kucha, Luntai and Kashgar in April and May 1912.[150]

The revolutionaries printed new multi-lingual media.[153]

Territorial uprisings

Tibet

In 1905, the Qing sent Zhao Erfeng to Tibet to retaliate against rebellions.[154] By 1908, Zhao was appointed imperial resident in Lhasa.[154] Zhao was beheaded in December 1911 by pro-Republican forces.[155] The bulk of the area historically known as Kham was now claimed to be the Xikang Administrative District, created by the Republican revolutionaries.[156] By the end of 1912, the last Qing troops were forced out of Tibet through India. Thubten Gyatso, the 13th Dalai Lama, returned to Tibet in January 1913 from Sikkim, where he had been residing. When the new ROC government apologized for the actions of the Qing and offered to restore the Dalai Lama to his former position, he replied he was not interested in Chinese ranks, that Tibet had never been subordinated to China, that Tibet was an independent country, and that he was assuming the spiritual and political leadership of Tibet. Because of this, many have read this reply as a formal declaration of independence. The Chinese side ignored the response, and Tibet had thirty years free of interference from China until 1951 and now Tibet is still ruled by China.[157]

Outer Mongolia

At the end of 1911, Outer Mongolians took action with an armed revolt against Qing authorities but were unsuccessful. The independence movement that took place was not limited to just Outer Mongolia but was a pan-Mongolian phenomenon.[158] On 29 December 1911, Bogd Khan became the ruler of the Bogd Khanate. Inner Mongolia became a contested terrain between the Bogd Khanate and China.[159] In general, Russia supported the independence of Outer Mongolia (including Tannu Uriankhai) during the time of the 1911 Revolution.[160]

Tibet and Outer Mongolia then recognized each other in a treaty. In 1919, the Republic of China regained Outer Mongolia but then lost it again in 1921. The People's Republic of China, a member of the United Nations, has officially recognized the independence of Outer Mongolia since 1949. Taiwan opened a cultural representative office and economy as part of their recognition of Mongolia in 2002.[citation needed]

Tannu Uriankhai secession

Change of government

North: Qing Court final transformation attempt

On 1 November 1911, the Qing government appointed Yuan Shikai as Prime Minister of the imperial cabinet, replacing Prince Qing.[161] On 3 November, after a proposition by Cen Chunxuan from the Constitutional Monarchy Movement, the Qing court passed the Nineteen Articles, which turned the Qing from an autocratic system with the emperor having unlimited power to a constitutional monarchy.[162][163] On 9 November, Huang Xing even cabled Yuan Shikai and invited him to join the Republic.[164] The court changes were too late, and the emperor was about to have to step down.

South: Provisional Government in Nanking

On 28 November 1911, Wuchang and Hanyang had fallen back to the Qing army. For safety, the revolutionaries convened their first conference at the British Concession in Hankou on 30 November.[165] By 2 December, the revolutionary forces were able to capture Nanking in the uprising; and the revolutionaries decided to make it the site of the new provisional government.[166] At the time, Beijing was still the Qing capital.

North–South Conference

On 18 December, the North–South Conference was held in Shanghai to discuss the north and south issues.[167] The reluctance of foreign financiers to give financial support to the Qing government or the revolutionaries contributed to both sides agreeing to start negotiations.[168] Yuan Shikai selected Tang Shaoyi as his representative.[167] Tang left Beijing for Wuhan to negotiate with the revolutionaries.[167] The revolutionaries chose Wu Tingfang.[167] With the intervention of six foreign powers, the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, Russia, Japan, and France, Tang Shaoyi and Wu Tingfang began to negotiate a settlement at the British concession.[169] Foreign businessman Edward Selby Little (李德立) acted as the negotiator and facilitated the peace agreement.[170] They agreed that Yuan Shikai would force the Qing emperor to abdicate in exchange for the southern provinces' support of Yuan as President of the Republic. After considering the possibility that the new republic might be defeated in a civil war or by foreign invasion, Sun Yat-sen agreed to Yuan's proposal to unify China under Yuan Shikai's Beijing government. Further decisions were made to let the emperor rule over his little court in the New Summer Palace. He would be treated as a ruler of a separate country and have expenses of several million taels in silver.[171]

Establishment of the Republic

Republic of China declared and national flag issued

On 29 December 1911, Sun Yat-sen was elected as the first provisional president. 1 January 1912 was set as the first day of the First Year of the ROC.[172] On 3 January, the representatives recommended Li Yuanhong as the Provisional Vice-president.[173]

During and after the 1911 Revolution, many groups that participated wanted their own pennant as the national flag. During the Wuchang Uprising, the military units of Wuchang wanted the nine-star flag with a taijitu.[174] Others in competition included Lu Haodong's Blue Sky with a White Sun flag. Huang Xing favored a flag bearing the mythical "well-field" system of village agriculture. In the end, the assembly compromised: the national flag would be the banner of Five Races Under One Union.[174] The Five Races Under One Union flag with horizontal stripes represented the five major nationalities of the republic.[175] The red represented Han, the yellow represented Manchus, the blue for Mongols, the white for Muslims, and the black for Tibetans.[174][175] Despite the general target of the uprisings to be the Manchus, Sun Yat-sen, Song Jiaoren and Huang Xing unanimously advocated racial integration to be carried out from the mainland to the frontiers.[176]

Donghuamen Incident

On 16 January, while returning to his residence, Yuan Shikai was ambushed in a bomb attack organized by the Tongmenghui in Donghuamen, Beijing.[177] Eighteen revolutionaries were involved. About ten guards died, but Yuan himself was not seriously injured.[177] He sent a message to the revolutionaries the next day pledging his loyalty and asking them not to organize any more assassination attempts against him.

Abdication of the Emperor

Zhang Jian drafted an abdication proposal that was approved by the Provisional Senate. On 20 January, Wu Tingfang of the Nanking Provisional Government officially delivered the Imperial Edict of Abdication to Yuan Shikai for the abdication of Puyi.[163] On 22 January, Sun Yat-sen announced that he would resign the presidency in favor of Yuan Shikai if the latter supported the emperor's abdication.[178] Yuan then pressured Empress Dowager Longyu with the threat that the imperial family's lives would not be spared if abdication did not come before the revolutionaries reached Beijing, but if they agreed to abdicate, the provisional government would honor the terms proposed by the imperial family.

On 3 February, Empress Dowager Longyu gave Yuan full permission to negotiate the abdication terms of the Qing emperor. Yuan then drew up his own version and forwarded it to the revolutionaries on 3 February.[163] His version consisted of three sections instead of two.[163] On 12 February, after being pressured by Yuan and other ministers, Puyi (age six) and Empress Dowager Longyu accepted Yuan's terms of abdication.[172]

Capital location debate

As a condition for ceding leadership to Yuan Shikai, Sun Yat-sen insisted that the provisional government remain in Nanjing. On 14 February, the Provisional Senate initially voted 20–5 in favor of making Beijing the capital over Nanjing, with two votes going for Wuhan and one for Tianjin. The Senate majority wanted to secure the peace agreement by taking power in Beijing. Zhang Jian and others reasoned that having the capital in Beijing would check against Manchu restoration and Mongol secession. But Sun and Huang Xing argued in favor of Nanjing to balance against Yuan's power base in the north. Li Yuanhong presented Wuhan as a compromise. The next day, the Provisional Senate voted again, this time, 19–6 in favor of Nanjing with two votes for Wuhan. Sun sent a delegation led by Cai Yuanpei and Wang Jingwei to persuade Yuan to move to Nanjing. Yuan welcomed the delegation and agreed to accompany the delegates back to the south. Then on the evening of 29 February, riots and fires broke out all over the city. They were allegedly started by disobedient troops of Cao Kun, a loyal officer of Yuan. The disorder gave Yuan the pretext to stay in the north to guard against unrest. On 10 March, Yuan was inaugurated in Beijing as the Provisional President of the Republic of China. On 5 April, the Provisional Senate in Nanjing voted to make Beijing the capital of the Republic and convened in Beijing at the end of the month.[179]

Republican Government in Beijing

On 10 March 1912, Yuan Shikai was sworn as the second Provisional President of the Republic of China in Beijing.[180] The first National Assembly election took place according to the Provisional Constitution. While in Beijing, the Kuomintang was formed on 25 August 1912.[181] The KMT held the majority of seats after the election. Song Jiaoren was elected as premier. However, Song was assassinated in Shanghai on 20 March 1913, under the secret order of Yuan Shikai.[182]

Proposed Han monarchy

Some advocated that an ethnic Han be installed as Emperor of China, either a descendant of Confucius who held the noble title of the Duke of Yansheng,[183][184][185][186][187] or a descendant of the Ming imperial family who possessed the title of the Marquis of Extended Grace.[188][189] The Duke of Yansheng was proposed as a candidate for emperorship by Liang Qichao.[190][better source needed]

The Han hereditary aristocratic nobility like the Duke of Yansheng were retained by the new Republic of China and the title holders continued to receive their pensions.

A plan backed by foreign bankers was reportedly in place to declare the Duke of Yansheng as Emperor of China, if the revolutionary's republican cause failed.[191]

Legacy

Social influence

| New Culture Movement |

|---|

|

|

After the revolution, there was a huge outpouring of anti-Manchu sentiment through China, but particularly in Beijing where thousands died in anti-Manchu violence. Imperial restrictions on Han residency and behavior within the city crumbled as Manchu imperial power crumbled.[192] Anti-Manchu sentiment is recorded in books like A Short History of Slaves (奴才小史) and The Biographies of Avaricious Officials and Corrupt Personnel (貪官污吏傳) by Laoli (老吏).[193][194][better source needed]

During the abdication of the last emperor, Empress Dowager Longyu, Yuan Shikai and Sun Yat-sen both tried to adopt the concept of "Manchu and Han as one family" (滿漢一家.[193] People started exploring and debating with themselves on the root cause of their national weakness. This new search of identity was the New Culture Movement.[195] Manchu culture and language, on the contrary, became virtually extinct by 2007.[196]

Unlike revolutions in the West, the 1911 Revolution did not restructure society. The participants in the 1911 Revolution were mostly military personnel, old-type bureaucrats, and local gentries. These people still held regional power after the 1911 Revolution. Some became warlords. There were no major improvements in the standard of living. The writer Lu Xun commented in 1921 during the publishing of The True Story of Ah Q, ten years after the 1911 Revolution, that basically nothing changed except "the Manchus have left the kitchen".[197] Economic problems were not addressed until the governance of Chiang Ching-kuo in Taiwan and Mao Zedong on the mainland.[198]

The 1911 Revolution mainly got rid of feudalism (fengjian) from the late imperial period. In the usual view of historians, there are two restorations of feudal power after the revolution: the first was Yuan Shikai; the second was Zhang Xun.[199] Due to the effects of anti-Manchu sentiment after the revolution, the Manchus of the Metropolitan Banners were driven into deep poverty, with Manchu men too impoverished to marry, so Han men married Manchu women, Manchus stopped dressing in Manchu clothing and stopped practicing Manchu traditions.[200]

Historical significance

The 1911 Revolution overthrew the Qing government and four thousand years of monarchy.[2] Throughout Chinese history, old dynasties had always been replaced by new dynasties. The 1911 Revolution, however, was the first to overthrow a monarchy completely and attempt to establish a republic to spread democratic ideas throughout China. In 1911 at the provisional government proclamation ceremony, Sun Yat-sen said, "The revolution is not yet successful, the comrades still need to strive for the future." (革命尚未成功,同志仍需努力).[201]

Since the 1920s, both the ROC and PRC have seen the 1911 Revolution quite differently.[202] Both Chinas recognize Sun Yat-sen as the Father of the Nation, but in Taiwan, they mean "Father of the Republic of China". On the mainland, Sun Yat-sen was seen as the man who helped bring down the Qing, a pre-condition for the Communist state founded in 1949. The PRC views Sun's work as the first step toward the real revolution in 1949, when the communists set up a truly independent state that expelled foreigners and built a military and industrial power. The father of New China is seen as Mao Zedong.[202] In 1954, Liu Shaoqi was quoted as saying that the "1911 Revolution inserted the concept of a republic into common people".[203][204] Zhou Enlai pointed out that the "1911 Revolution overthrew the Qing rule, ended 4,000 years of monarchy, and liberated the mind of people to a great extent, and opened up the path for the development of future revolution. This is a great victory."[205]

Modern evaluation

A change in the belief that the revolution had been a generally positive change began in the late 1980s and 1990s, but Zhang Shizhao was quoted as arguing that "When talking about the 1911 Revolution, the theorist these days tends to overemphasize. The word 'success' was way overused."[206]

The degree of success of democracy gained by the revolution can vary depending on one's view. Even after Sun Yat-sen died in 1925, for sixty years, the KMT controlled all five branches of the government; none were independent.[198] Yan Jiaqi, founder of the Federation for a Democratic China, has said that Sun Yat-sen is to be credited as founding China's first republic in 1912, and the second republic is the people of Taiwan and the political parties there now democratizing the region.[199]

Meanwhile, the ideals of democracy are far from realised on the mainland Chinese side. For example, former Chinese premier Wen Jiabao once said in a speech that without real democracy, there is no guarantee of economic and political rights; but he led a 2011 crackdown against the peaceful Chinese jasmine protests.[207] Others, such as Qin Yongmin of the Democracy Party of China, who was imprisoned for twelve years, do not praise the 1911 Revolution.[208][209][better source needed] Qin said the revolution only replaced one dictator with another, that Mao was not an emperor, but he is worse than the emperor.[208][209][210]

Media

One of Japan's earliest film companies (M. Pathe, owned by Sun supporter Shōkichi Umeya) documented the success of the revolution beginning with the Wuchang uprising and leading to Sun's inauguration, producing three documentary films that covered the revolution.[211]

See also

- 1911 (film)

- The Battle for the Republic of China

- Republic of China Armed Forces

- Republic of China calendar

- National Revolutionary Army

- Timeline of late anti-Qing rebellions

- Qiu Jin

- Monarchy of China

Notes

References

- ^ Chan Lau, Kit-ching (1978). Anglo-Chinese Diplomacy 1906–1920: In the Careers of Sir John Jordan and Yuan Shih-kai. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-9-6220-9010-1.

- ^ a b c Li, Xiaobing (2007). A History of the Modern Chinese Army. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 13, 26–27. ISBN 978-0-8131-2438-4.

- ^ Li, Xing (2010). The Rise of China and the Capitalist World Order. Ashgate. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-7546-7913-4.

- ^ a b c Wang 1998, pp. 106, 344.

- ^ a b Bevir, Mark (2010). Encyclopedia of Political Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-4129-5865-3.

- ^ Chang, Kang-i Sun; Owen, Stephen (2010). The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-5211-1677-0.

- ^ Dianda, Bas (2019). Political Routes to Starvation: Why Does Famine Kill?. Vernon. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-6227-3508-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Hong Kong played a key role in the life of Sun Yat-sen". South China Morning Post. 29 March 2011.

- ^ Lum, Yansheng Ma; Lum, Raymond Mun Kong (1999). Sun Yat-sen in Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-8248-2179-1.

- ^ Curthoys, Ann; Lake, Marilyn (2005). Connected Worlds: History in Transnational Perspective. Canberra: ANU E Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-920942-44-1.

- ^ Platt, Stephen R. (2007). Provincial Patriots: The Hunanese and Modern China. Harvard University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-6740-2665-0.

- ^ Goossaert, Vincent; Palmer, David A. (2011). The Religious Question in Modern China. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-30416-8.

- ^ a b Wang 1998, p. 287.

- ^ a b 計秋楓, 朱慶葆. (2001). 中國近代史, V. 1. Chinese University Press. ISBN 978-9-6220-1987-4. p. 468.

- ^ Etō, Shinkichi; Schiffrin, Harold Z. (1994). China's Republican Revolution. University of Tokyo Press. ISBN 978-4-13-027030-4.

- ^ Wong, Wendy Siuyi. (2001) Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua. Princeton Architectural Press. New York. ISBN 1-5689-8269-0

- ^ 为君丘, 張運宗. (2003). 走入近代中國. 五南圖書出版股份有限公司. ISBN 9789571131757.

- ^ 蔣緯國. (1981). 建立民國, Vol. 2. 國民革命戰史: 第1部. 黎明文化事業公司. University of California. Digitized 14 February 2011.

- ^ 饒懷民. (2006). 辛亥革命與清末民初社會/中國近代史事論叢. 中華書局 publishing. ISBN 978-7-1010-5156-8.

- ^ a b Wang 1998, pp. 390–391.

- ^ a b 張豈之, 陳振江, 江沛. (2002). 晚淸民國史. Volume 5 of 中國歷史, 張 豈之. 五南圖書出版股份有限公司. ISBN 978-9-5711-2898-6. pp. 178–186

- ^ 蔡登山. 繁華落盡──洋場才子與小報文人. 秀威資訊科技股份有限公司. ISBN 978-9-8622-1826-6. p. 42.

- ^ Scalapino, Robert A.; Yu, George T. (1961). The Chinese Anarchist Movement. Berkeley: Center for Chinese Studies, Institute of International Studies, University of California. At The Anarchist Library (Free Download). The online version is unpaginated.

- ^ 楊碧玉. 洪秀全政治人格之研究. 秀威資訊科技股份有限公司 Publishing. ISBN 978-9-8622-1141-0.

- ^ Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1990). Orphan Warriors. Princeton University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-691-00877-6.

- ^ Lee, Khoon Choy (2005). Pioneers of Modern China. World Scientific. ISBN 981-256-618-X.

- ^ a b Gao 2009, pp. 29, 156.

- ^ a b Fenby 2008, pp. 96, 106.

- ^ Fenby 2008, p. 109.

- ^ Complete works of Sun Yat-sen 《總理全集》 1st ed., p. 920

- ^ Rhoads 2017, p. 21.

- ^ Wang 1998, p. 76.

- ^ Kaplan, Lawrence M. (2010). Homer Lea American Soldier of Fortune. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2617-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Lau, Kit-ching Chan (1990). China, Britain and Hong Kong, 1895–1945. Chinese University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-9-6220-1409-1.

- ^ Borst-Smith, Ernest F. (1912). Caught in the Chinese Revolution. T. Fisher Unwin.

- ^ Nash, Jay Robert (1997). Spies: A Narrative Encyclopedia of Dirty Tricks and Double Dealing from Biblical Times to Today. M. Evans. pp. 99ff. ISBN 978-1-4617-4770-3.

- ^ Bergère, Marie-Claire; Lloyd, Janet (1998). Sun Yat-sen. Stanford University Press. pp. 132. ISBN 978-0-8047-4011-1.

- ^ Horne, Gerald (2005). Race War!: White Supremacy and the Japanese Attack on the British Empire. New York University Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-8147-3641-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chung, Dooeum (2000). Élitist fascism: Chiang Kaishek's Blueshirts in 1930s China. Ashgate. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7546-1166-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chung, Dooeum (1997). A re-evaluation of Chiang Kaishek's blueshirts: Chinese fascism in the 1930s. University of London. p. 78 – via Google Books.

- ^ Carlisle, Rodney (2015). Encyclopedia of Intelligence and Counterintelligence. Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-3174-7177-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Spence, Jonathan D. (1990). The Search for Modern China. W.W. Norton. pp. 250–256. ISBN 0-3933-0780-8.

- ^ 計秋楓, 朱慶葆. (2001). 中國近代史, Vol. 1. Chinese University Press. ISBN 978-9-6220-1987-4. p. 464.

- ^ South China Morning Post. 6 April 2011. Waiting may be over at the grave of an unsung hero.

- ^ Wang 1998, p. 424.

- ^ Gao 2009, Chronology section.

- ^ 陳錫祺. (1991). 孫中山年谱長編 Vol. 1. 中华书局. ISBN 978-7-1010-0685-8.

- ^ 申友良. (2002). 报王黃世仲. 中囯社会科学出版社 publishing. ISBN 978-7-5004-3309-5.

- ^ Judge, Joan (1996). Print and politics: 'Shibao' and the culture of reform in late Qing China. Stanford University Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-8047-2741-9.

- ^ 清宮藏辛亥革命檔案公佈 清廷密追孫中山(圖)-新聞中心_中華網 [Archives of the 1911 Revolution in the Palace Collection of the Qing Dynasty Released]. China.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ a b 張家鳳. (2010). 中山先生與國際人士. Vol. 1. 秀威資訊科技股份有限公司. ISBN 978-9-8622-1510-4. p. 195.

- ^ 公元1907年5月27日 黄冈起义失败 [On May 27, 1907, the Huanggang Uprising failed.]. Baojinews.com (in Chinese). 27 May 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ 張豈之, 陳振江, 江沛. (2002). 晚淸民國史. Volume 5 of 中國歷史. 五南圖書出版股份有限公司 publishing. ISBN 978-9-5711-2898-6. p. 177.

- ^ a b 中国二十世紀通鉴编辑委员会. (2002). 中国二十世紀通鉴, 1901–2000, Vol. 1. 线装書局.

- ^ a b c Lu, Xun (2009). Capturing Chinese (in Chinese). Capturing Chinese. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-9842762-0-2.

- ^ 鄭連根. (2009). 故紙眉批── 一個傳媒人的讀史心得. 秀威資訊科技股份有限公司 publishing. ISBN 978-9-8622-1190-8. p. 135.

- ^ a b c 辛亥革命武昌起義紀念館. (1991). 辛亥革命史地圖集. 中國地圖出版社 publishing.

- ^ 中華民國史硏究室. (1986). 中華民國史資料叢稿: 譯稿. Volumes 1–2 of 中華民國史資料叢稿. published by 中華書局.

- ^ Yan, Qinghuang. (2008). The Chinese in Southeast Asia and Beyond: Socioeconomic and Political Dimensions. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-9-8127-9047-7. pp. 182–187.

- ^ 廣西壯族自治區地方誌編纂委員會. (1994). 廣西通志: 軍事志. 廣西人民出版社 publishing. Digitized University of Michigan. 2009.

- ^ 中国百科年鉴. (1982). 中国大百科全书出版社. University of California. Digitized 2008.

- ^ 汪贵胜, 许祖范. Compiled by 程必定. (1989). 安徽近代经济史. 黄山书社. Digitized by the University of Michigan. 2007.

- ^ 张新民. (1993). 中国人权辞书. 海南出版社 publishing. Digitized by University of Michigan. 2009.

- ^ a b 王恆偉. (2005) (2006) 中國歷史講堂 No. 5 清. 中華書局. ISBN 9-6288-8528-6. pp. 195–198.

- ^ a b Langmead, Donald (2011). Maya Lin. Santa Barbara, Calif: Greenwood. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-313-37853-9.

- ^ Reilly, Thomas. (1997). Science and Football III, Vol. 3. Taylor & Francis publishing. ISBN 978-0-4192-2160-9. pp. 105–106, 277–278.

- ^ Robert H. Felsing (1979). The heritage of Han: the Gelaohui and the 1911 revolution in Sichuan. University of Iowa. p. 156. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

The railway company's chief officer at Yichang was no longer listening to company directives and had turned company accounts over to Duanfang, Superintendent of the Chuan Han and Yue Han railroads. The situation of the Sichuanese

- ^ a b 王恆偉. [2005] (2006) 中國歷史講堂 No. 6 民國. 中華書局. ISBN 9-6288-8529-4. pp. 3–7.

- ^ a b c d 戴逸, 龔書鐸. (2003) 中國通史. 清. Intelligence Press. ISBN 9-6287-9289-X. pp. 86–89.

- ^ Thomson, John Stuart (1913). China Revolutionized. Bobbs-Merrill Company. p. 59. ISBN 9-3539-7226-4.

- ^ Thomson 1913, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e 张创新. (2005). 中国政治制度史. 2nd ed., Tsinghua University Press. ISBN 978-7-3021-0146-8. p. 377.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l 武昌起義之後各省響應與國際調停 _新華網湖北頻道 (in Chinese). Xinhua. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Backhouse, Edmund; Otway, John; Bland, Percy (1914). Annals & Memoirs of the Court of Peking: (from the 16th to the 20th Century) (Repr. ed.). Houghton Mifflin. p. 209.

- ^ The Atlantic. Vol. 112. Atlantic Monthly. 1913. p. 779.

- ^ a b Lipman, Jonathan N. (1998). Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-2959-7644-0. OL 8580403W.

- ^ Rhoads 2017, pp. 190–193.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Charles Patrick; Kotker, Norman (1969). Kotker, Norman (ed.). The Horizon history of China (Illustrated ed.). American Heritage. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-8281-0005-2.

- ^ Lipman 1998, p. 170, "Ma Anliang attacked Shaanxi successfully, and Yuan Shikai took the invasion seriously enough to alert eastern troops to move against him.".

- ^ Shan, Patrick Fuliang (2018). Yuan Shikai: A Reappraisal. Contemporary Chinese Studies. UBC Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-7748-3781-1.

On his order, Wang was executed.66 According to Yuan Shikai, the most important ... to arrest bad elements and protect the people (chubao'anliang), ...

- ^ Israeli, Raphael (2017). The Muslim Midwest in Modern China: The Tale of the Hui Communities in Gansu (Lanzhou, Linxia, and Lintan) and in Yunnan (Kunming and Dali). Wipf & Stock. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-1-5326-3754-4.

This message by Wang may have contributed to breaking the resistance of Ma Anliang, who had in any case, come under strong pressure of Yuan Shikai's ...

- ^ Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1980). The Border World of Gansu, 1895–1935. Stanford University PRess. pp. 105, 208–209.

... White Wolf and the "Hui protector and mediator," Ma Anliang. When Yuan Shikai died in 1916, Zhang Guangjian's control over Gansu did not decrease .

- ^ Frankel, James (2021). Islam in China. Islam in Series. Bloomsbury. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7556-3884-0.

... thereupon supporting Yuan Shikai even when he declared himself emperor. Despite their close relationship, when his superior Ma Anliang tried to arrest ...

- ^ Mühlhahn, Klaus (2014). Herrschaft und Widerstand in der "Musterkolonie" Kiautschou: Interaktionen zwischen China und Deutschland, 1897–1914. Studien zur Internationalen Geschichte. Vol. 8 (ill. ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 399. ISBN 978-3-4867-1369-5.

tierte Yuan Shikai in bezug auf die Boxerbewegung, daß "Irrlehren (yaoyan) ... Revolte Ruhe und Frieden eintreten können" (chu bao nai ke anliang gaoshi).

- ^ Mueggler, Erik (2011). The Paper Road: Archive and Experience in the Botanical Exploration of West China and Tibet (Illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-5202-6902-6.

When that army's commander, Dong Fuxiang died in 1908, Ma Anliang took control ... To curb the power of these warlords, Yuan Shikai sent his subordinates to ...

- ^ Jowett, Philip (2013). China's Wars: Rousing the Dragon 1894–1949 (Ill. ed.). Bloomsbury. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4728-0674-1.

During the Second Revolution in 1913 he was persuaded by the southern Revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen to join the anti-Yuan Shikai rebellion.

- ^ Hamrin, Carol Lee (2009). Hamrin, Carol Lee; Bieler, Stacey (eds.). Salt and Light, Vol. 1: Lives of Faith That Shaped Modern China. Studies in Chinese Christianity. Wipf & Stock. ISBN 978-1-6218-9291-5.

Yuan Shikai, later to become the first President of the Republic of China, was in charge of foreign affairs (and much else) for this last decade of the ...

- ^ Shan, Patrick Fuliang (2018). Yuan Shikai: A Reappraisal. Contemporary Chinese Studies. University of British Columbia Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-7748-3781-1.

On his order, Wang was executed.66 According to Yuan Shikai, the most important ... to arrest bad elements and protect the people (chubao'anliang), ...

- ^ Dillon, Michael (2013). China's Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-1368-0933-0.

... poor' and 'Down with Yuan Shikai,' the first president of the new Chinese ... Ma Anliang sent his subordinate Ma Qi to the old town of Taozhou on April ...

- ^ Sahay, R.K. (2016). History of China's Military (Illustrated ed.). Vij Books India Pvt. ISBN 978-9-3860-1990-5.

... commanders such as Zeng Guofan, Zuo Zongtang, Li Hongzhang and Yuan Shikai. ... Ma Anliang, Ma Fuxiang, and Ma Fuxing who commanded the Kansu Braves.

- ^ Esherick, Joseph W. (2022). Accidental Holy Land: The Communist Revolution in Northwest China (Illustrated ed.). University of California Press. pp. 29, 197. ISBN 978-0-5203-8532-0.

- ^ —— (2022). Accidental Holy Land: The Communist Revolution in Northwest China. University of California Press. pp. 29, 197. doi:10.1525/luminos.117. ISBN 978-0-5203-8532-0. S2CID 244639814.

- ^ Esherick, Joseph W. (2022). Accidental Holy Land: The Communist Revolution in Northwest China (Illustrated ed.). Univ of California Press. p. 197. doi:10.1525/luminos.117. ISBN 978-0-5203-8532-0. S2CID 244639814.

- ^ Rhoads 2017, p. 204.

- ^ Li, Xue (2018). Making Local China: A Case Study of Yangzhou, 1853–1928. Berliner China-Studien. Vol. 56. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 237. ISBN 978-3-6439-0894-0.

- ^ Shan, Patrick Fuliang (2018). Yuan Shikai: A Reappraisal. Contemporary Chinese Studies. University of British Columbia Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-7748-3781-1.

- ^ Witchard, Anne (2012). Lao She in London. RAS China in Shanghai series of China Monographs. Vol. 1 (Illustrated ed.). Hong Kong University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-9-8881-3960-6.

- ^ Harper, Tim (2021). Underground Asia: Global Revolutionaries and the Assault on Empire. Harvard University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-6747-2461-7.

- ^ China's Millions, Issues 79–90. Morgan and Scott. 1882. p. 113.

- ^ Broomhall, Marshall (1907). The Chinese Empire: A General and Missionary Survey, Vol. 678–679. The Chinese Empire: A General and Missionary Survey, Marshall Broomhall. Morgan at Scott. p. 201.

- ^ The Chinese Empire. p. 201.

- ^ China's Millions. Vol. 28. China Inland Mission. 1902. p. 18.

- ^ Schinz, Alfred (1996). The Magic Square: Cities in Ancient China (Ill. ed.). Edition Axel Menges. p. 354. ISBN 3-9306-9802-1.

- ^ Borst-Smith, Ernest F. (1912). Caught in the Chinese revolution: a record of risks and rescue. London: T. Fisher Unwin. pp. 19–21.

- ^ Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (1980). The Border World of Gansu, 1895–1935. Stanford University. p. 184.

Sheng Yun , a Manchu , and Chang Geng , a life bondservant of the Qing house , agreed that an attack had to be undertaken swiftly , so Ma was ... Chang needed the Hui , and that meant trusting the loyalty of Ma Anliang and Ma Fuxiang .

- ^ National Review: Zhongguo Gong Lun Xi Bao, Vol. 14. 1913. p. 251.

... will enter the Ministry of Commerce which will be A Peking telegram also states that Sheng Yun , the reorganized ... where is alleged to be coTsen Chun – hsuan . operating with General Ma An – liang in stirring up The " Peking Jih ...

- ^ Lipman 1998, p. 170.

- ^ Teichman, Eric (1921). Travels of a Consular officer in North West China; with original maps of Shensi and Kansu and illus. by photographs. Cambridge University Press. pp. 120–122.

- ^ The National Review, China: Literary and educational supplement, Vol. 15. National Review. 1914. p. 482.

General Ma An-liang to take his Muhammadan requesting that the disbandment be postponed troops to Fenghsiangfu and ... also that all latter reached Sianfu by forced marches from asking for information regarding the statements local ...

- ^ Keyte, J. C. (1924). Andrew Young of Shensi :Adventure in Medical Missions (PDF). London: The Carey Press. p. vi.

- ^ Thomson 1913, p. 64.

- ^ Thomson 1913, p. 46.

- ^ Thomson 1913, p. 53.

- ^ Thomson 1913, p. 37, On October 24th, ancient Singan the capital of the northwestern province of Shensi, the original capital of China, where the empress dowager, Tse Hsi.

- ^ Japan Weekly Mail. 1905. p. 206.

That degradation of H. E. Sheng Yun, Governor of Shensi, A Peking correspondent, writing about the recent was delayed some three hours. A telegram was received on Feb. 18th in Japanese adventurers should be serving with to ihe post ...

- ^ Lipman 1998, p. 263.

- ^ Thomson 1913, pp. 71, 449.

- ^ Lipman 1998, pp. 171–172.

- ^ "中華民國海軍 – 旗海圖幟". Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m 伍立杨. (2011). 中国1911 (辛亥年). ISBN 978-7-5313-3869-7. Chapter 连锁反应 各省独立.

- ^ 辛亥革命中的九江起义(3) (in Chinese). xhgmw.com. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ 蒋顺兴, 李良玉. (1990). 山西王阎锡山/中华民国史丛书. Edition reprint. 河南人民出版社, 1990.

- ^ Remote Homeland, Recovered Borderland: Manchus, Manchoukuo, and Manchuria, 1907–1985. p. 102.

- ^ 山西辛亥革命官僚階層——巡撫陸鍾琦之死_辛亥革命前奏_辛亥革命网 (in Chinese). Big5.xhgmw.org. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ 中共湖南省委員會. (1981). 新湘評論, Issues 7–12. 新湘評論雜誌社.

- ^ "四大家族"后人:蒋家凋零落寞 宋、孔、陈家低调 (in Chinese). Chinanews.com.cn. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ 张玉法, 中央硏究院. 近代史硏究所. (1985). 民国初年的政党. 中央硏究院近代史硏究所 Publishing.

- ^ 辛亥百年蘇州光復一根竹竿挑瓦革命 (in Chinese). Xinhua. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Rhoads 2017, p. 194.

- ^ 辛亥革命大事記_時政頻道_新華網. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ 温馨提示 (in Chinese).

- ^ 國立臺灣師範大學. 歷史學系. (2003). Bulletin of historical research, Issue 31. 國立臺灣師範大學歷史學系 publishing.

- ^ Lary, Diana (2010). Warlord Soldiers: Chinese Common Soldiers 1911–1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-521-13629-7.

- ^ Boorman, Howard L.; Howard, Richard C.; Cheng, Joseph K. H. (1967). Biographical Dictionary of Republican China. Columbia University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-2310-8957-9.

pai ch'ung-hsi dare to die.

- ^ a b c 国祁李. (1990). 民国史论集, Volume 2. 南天書局 publishing.

- ^ (1979). 傳記文學, Volume 34. 傳記文學雜誌社 Publishing. University of Wisconsin– Madison. Digitized 11 April 2011.

- ^ Deng Zhicheng (鄧之誠) (1988). 中華二千年史 (in Chinese). Vol. 5. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. ISBN 978-7-101-00390-1. . (1983). , Volume 5, Part 3, Issue 1. 中華書局. ISBN 978-7-1010-0390-1.

- ^ 广东省中山图书馆. (2002). 民国广东大事记. 羊城晚报出版社 Publishing. ISBN 978-7-8065-1206-7.

- ^ a b 徐博东, 黄志萍. (1987). 丘逢甲傳. 秀威資訊科技股份有限公司 publishing. ISBN 978-9-8622-1636-1. p. 175.

- ^ 居正, 羅福惠, 蕭怡. (1989). 居正文集, Volume 1. 華中師範大學出版社 publishing. Digitized by University of California. 15 December 2008.