Half-life

| Number of half-lives elapsed |

Fraction remaining |

Percentage remaining | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1⁄1 | 100 | |

| 1 | 1⁄2 | 50 | |

| 2 | 1⁄4 | 25 | |

| 3 | 1⁄8 | 12 | .5 |

| 4 | 1⁄16 | 6 | .25 |

| 5 | 1⁄32 | 3 | .125 |

| 6 | 1⁄64 | 1 | .5625 |

| 7 | 1⁄128 | 0 | .78125 |

| n | 1⁄2n | 100⁄2n | |

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| mathematical constant e |

|---|

|

| Properties |

| Applications |

| Defining e |

| People |

| Related topics |

Half-life (symbol t½) is the time required for a quantity (of substance) to reduce to half of its initial value. The term is commonly used in nuclear physics to describe how quickly unstable atoms undergo radioactive decay or how long stable atoms survive. The term is also used more generally to characterize any type of exponential (or, rarely, non-exponential) decay. For example, the medical sciences refer to the biological half-life of drugs and other chemicals in the human body. The converse of half-life (in exponential growth) is doubling time.

The original term, half-life period, dating to Ernest Rutherford's discovery of the principle in 1907, was shortened to half-life in the early 1950s.[1] Rutherford applied the principle of a radioactive element's half-life in studies of age determination of rocks by measuring the decay period of radium to lead-206.

Half-life is constant over the lifetime of an exponentially decaying quantity, and it is a characteristic unit for the exponential decay equation. The accompanying table shows the reduction of a quantity as a function of the number of half-lives elapsed.

Probabilistic nature

[edit]

A half-life often describes the decay of discrete entities, such as radioactive atoms. In that case, it does not work to use the definition that states "half-life is the time required for exactly half of the entities to decay". For example, if there is just one radioactive atom, and its half-life is one second, there will not be "half of an atom" left after one second.

Instead, the half-life is defined in terms of probability: "Half-life is the time required for exactly half of the entities to decay on average". In other words, the probability of a radioactive atom decaying within its half-life is 50%.[2]

For example, the accompanying image is a simulation of many identical atoms undergoing radioactive decay. Note that after one half-life there are not exactly one-half of the atoms remaining, only approximately, because of the random variation in the process. Nevertheless, when there are many identical atoms decaying (right boxes), the law of large numbers suggests that it is a very good approximation to say that half of the atoms remain after one half-life.

Various simple exercises can demonstrate probabilistic decay, for example involving flipping coins or running a statistical computer program.[3][4][5]

Formulas for half-life in exponential decay

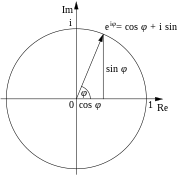

[edit]An exponential decay can be described by any of the following four equivalent formulas:[6]: 109–112 where

- N0 is the initial quantity of the substance that will decay (this quantity may be measured in grams, moles, number of atoms, etc.),

- N(t) is the quantity that still remains and has not yet decayed after a time t,

- t½ is the half-life of the decaying quantity,

- τ is a positive number called the mean lifetime of the decaying quantity,

- λ is a positive number called the decay constant of the decaying quantity.

The three parameters t½, τ, and λ are directly related in the following way:where ln(2) is the natural logarithm of 2 (approximately 0.693).[6]: 112

Half-life and reaction orders

[edit]In chemical kinetics, the value of the half-life depends on the reaction order:

Zero order kinetics

[edit]The rate of this kind of reaction does not depend on the substrate concentration, [A]. Thus the concentration decreases linearly.

- The integrated rate law of zero order kinetics is:

In order to find the half-life, we have to replace the concentration value for the initial concentration divided by 2: and isolate the time:This t½ formula indicates that the half-life for a zero order reaction depends on the initial concentration and the rate constant.

First order kinetics

[edit]In first order reactions, the rate of reaction will be proportional to the concentration of the reactant. Thus the concentration will decrease exponentially. as time progresses until it reaches zero, and the half-life will be constant, independent of concentration.

The time t½ for [A] to decrease from [A]0 to 1/2[A]0 in a first-order reaction is given by the following equation:It can be solved forFor a first-order reaction, the half-life of a reactant is independent of its initial concentration. Therefore, if the concentration of A at some arbitrary stage of the reaction is [A], then it will have fallen to 1/2[A] after a further interval of Hence, the half-life of a first order reaction is given as the following:

The half-life of a first order reaction is independent of its initial concentration and depends solely on the reaction rate constant, k.

Second order kinetics

[edit]In second order reactions, the rate of reaction is proportional to the square of the concentration. By integrating this rate, it can be shown that the concentration [A] of the reactant decreases following this formula:

We replace [A] for 1/2[A]0 in order to calculate the half-life of the reactant A and isolate the time of the half-life (t½):This shows that the half-life of second order reactions depends on the initial concentration and rate constant.

Decay by two or more processes

[edit]Some quantities decay by two exponential-decay processes simultaneously. In this case, the actual half-life T½ can be related to the half-lives t1 and t2 that the quantity would have if each of the decay processes acted in isolation:

For three or more processes, the analogous formula is: For a proof of these formulas, see Exponential decay § Decay by two or more processes.

Examples

[edit]There is a half-life describing any exponential-decay process. For example:

- As noted above, in radioactive decay the half-life is the length of time after which there is a 50% chance that an atom will have undergone nuclear decay. It varies depending on the atom type and isotope, and is usually determined experimentally. See List of nuclides.

- The current flowing through an RC circuit or RL circuit decays with a half-life of ln(2)RC or ln(2)L/R, respectively. For this example the term half time tends to be used rather than "half-life", but they mean the same thing.

- In a chemical reaction, the half-life of a species is the time it takes for the concentration of that substance to fall to half of its initial value. In a first-order reaction the half-life of the reactant is ln(2)/λ, where λ (also denoted as k) is the reaction rate constant.

In non-exponential decay

[edit]The term "half-life" is almost exclusively used for decay processes that are exponential (such as radioactive decay or the other examples above), or approximately exponential (such as biological half-life discussed below). In a decay process that is not even close to exponential, the half-life will change dramatically while the decay is happening. In this situation it is generally uncommon to talk about half-life in the first place, but sometimes people will describe the decay in terms of its "first half-life", "second half-life", etc., where the first half-life is defined as the time required for decay from the initial value to 50%, the second half-life is from 50% to 25%, and so on.[7]

In biology and pharmacology

[edit]A biological half-life or elimination half-life is the time it takes for a substance (drug, radioactive nuclide, or other) to lose one-half of its pharmacologic, physiologic, or radiological activity. In a medical context, the half-life may also describe the time that it takes for the concentration of a substance in blood plasma to reach one-half of its steady-state value (the "plasma half-life").

The relationship between the biological and plasma half-lives of a substance can be complex, due to factors including accumulation in tissues, active metabolites, and receptor interactions.[8]

While a radioactive isotope decays almost perfectly according to first order kinetics, where the rate constant is a fixed number, the elimination of a substance from a living organism usually follows more complex chemical kinetics.

For example, the biological half-life of water in a human being is about 9 to 10 days,[9] though this can be altered by behavior and other conditions. The biological half-life of caesium in human beings is between one and four months.

The concept of a half-life has also been utilized for pesticides in plants,[10] and certain authors maintain that pesticide risk and impact assessment models rely on and are sensitive to information describing dissipation from plants.[11]

In epidemiology, the concept of half-life can refer to the length of time for the number of incident cases in a disease outbreak to drop by half, particularly if the dynamics of the outbreak can be modeled exponentially.[12][13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ John Ayto, 20th Century Words (1989), Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Muller, Richard A. (April 12, 2010). Physics and Technology for Future Presidents. Princeton University Press. pp. 128–129. ISBN 9780691135045.

- ^ Chivers, Sidney (March 16, 2003). "Re: What happens during half-lifes [sic] when there is only one atom left?". MADSCI.org.

- ^ "Radioactive-Decay Model". Exploratorium.edu. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ Wallin, John (September 1996). "Assignment #2: Data, Simulations, and Analytic Science in Decay". Astro.GLU.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-09-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Rösch, Frank (September 12, 2014). Nuclear- and Radiochemistry: Introduction. Vol. 1. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-022191-6.

- ^ Jonathan Crowe; Tony Bradshaw (2014). Chemistry for the Biosciences: The Essential Concepts. OUP Oxford. p. 568. ISBN 9780199662883.

- ^ Lin VW; Cardenas DD (2003). Spinal cord medicine. Demos Medical Publishing, LLC. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-888799-61-3.

- ^ Pang, Xiao-Feng (2014). Water: Molecular Structure and Properties. New Jersey: World Scientific. p. 451. ISBN 9789814440424.

- ^ Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (31 March 2015). "Tebufenozide in the product Mimic 700 WP Insecticide, Mimic 240 SC Insecticide". Australian Government. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Fantke, Peter; Gillespie, Brenda W.; Juraske, Ronnie; Jolliet, Olivier (11 July 2014). "Estimating Half-Lives for Pesticide Dissipation from Plants". Environmental Science & Technology. 48 (15): 8588–8602. Bibcode:2014EnST...48.8588F. doi:10.1021/es500434p. hdl:20.500.11850/91972. PMID 24968074.

- ^ Balkew, Teshome Mogessie (December 2010). The SIR Model When S(t) is a Multi-Exponential Function (Thesis). East Tennessee State University.

- ^ Ireland, MW, ed. (1928). The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War, vol. IX: Communicable and Other Diseases. Washington: U.S.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 116–7.

External links

[edit]- https://www.calculator.net/half-life-calculator.html Comprehensive half-life calculator

- wiki: Decay Engine, Nucleonica.net (archived 2016)

- System Dynamics – Time Constants, Bucknell.edu

- Researchers Nikhef and UvA measure slowest radioactive decay ever: Xe-124 with 18 billion trillion years

- https://academo.org/demos/radioactive-decay-simulator/ Interactive radioactive decay simulator demonstrating how half-life is related to the rate of decay

![{\displaystyle d[{\ce {A}}]/dt=-k}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e0d11a976526a07f717c25cd724e2544a4ee5649)

![{\displaystyle [{\ce {A}}]=[{\ce {A}}]_{0}-kt}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8a8d0e16353886b89240f30b9f54cdc7a4149786)

![{\displaystyle [{\ce {A}}]_{0}/2=[{\ce {A}}]_{0}-kt_{1/2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/826087aba9042219c8eef066b73bc9c2fefcb904)

![{\displaystyle t_{1/2}={\frac {[{\ce {A}}]_{0}}{2k}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f4eca8d1ce264cb32692257294eca4fcc00c0866)

![{\displaystyle [{\ce {A}}]=[{\ce {A}}]_{0}\exp(-kt)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e66d0ac1acaa8904f02364bd2a42163fd0c45757)

![{\displaystyle [{\ce {A}}]_{0}/2=[{\ce {A}}]_{0}\exp(-kt_{1/2})}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7ca0db5cf3bfaac58a98000354a6a9d3bd72f5eb)

![{\displaystyle kt_{1/2}=-\ln \left({\frac {[{\ce {A}}]_{0}/2}{[{\ce {A}}]_{0}}}\right)=-\ln {\frac {1}{2}}=\ln 2}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/082b3f6dc924c53343aacf4e0a58112958cd6824)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{[{\ce {A}}]}}=kt+{\frac {1}{[{\ce {A}}]_{0}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ee6d34dbb3bff34a51b42cc06ab317aace3dfa08)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{[{\ce {A}}]_{0}/2}}=kt_{1/2}+{\frac {1}{[{\ce {A}}]_{0}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ff43700aeca7595315c4fd1c4cf3798288d887b0)

![{\displaystyle t_{1/2}={\frac {1}{[{\ce {A}}]_{0}k}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/842dfc3b12854a4d7a822b58337efed28b8cc82a)