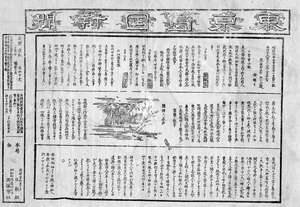

Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (January 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun (東京日日新聞, Tōkyō Nichi Nichi Shinbun) (lit. Tokyo Daily News) was a newspaper printed in Tokyo, Japan from 1872 to 1943.

In 1875, the company began the world's first newspaper delivery service.

In 1911, the paper merged with Osaka Mainichi Shimbun (大阪毎日新聞, lit. Osaka Daily News) to form the Mainichi Shimbun (毎日新聞, lit. "Daily News") company. The two newspapers continued to print independently until 1943, when both editions were placed under a Mainichi Shimbun masthead.

Sino-Japanese War coverage controversy

[edit]

In 1937, the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun and its sister newspaper, the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, covered a contest between two Japanese officers, Toshiaki Mukai (向井 敏明) and Tsuyoshi Noda (野田 毅), in which the two men were described as vying with one another to be the first to kill 100 people with a sword. The competition supposedly took place en route to Nanjing prior to the infamous Nanjing Massacre, and was covered in four articles from 30 November 1937, to 13 December 1937; the last two being translated in the Japan Advertiser.

Both officers supposedly surpassed their goal during the heat of battle, making it difficult to determine which officer had actually won the contest. Therefore, according to the journalists Asami Kazuo and Suzuki Jiro, writing in the Tokyo Nichi-Nichi Shimbun of 13 December, they decided to begin another contest with the goal of 150 kills.[1] The Nichi Nichi headline of the story of 13 December read "'Incredible Record' [in the Contest to] Behead 100 People—Mukai 106 – 105 Noda—Both 2nd Lieutenants Go Into Extra Innings".

Other soldiers and historians have noted the improbability of the lieutenants' alleged heroics, which entailed killing enemy after enemy in fierce hand-to-hand combat.[2] Noda himself, on returning to his hometown, admitted this during a speech that "I killed only four or five with sword in the real combat ... After we captured an enemy trench, we'd tell them, 'Ni Lai Lai.'[note 1] The Chinese soldiers were stupid enough to come out the trench toward us one after another. We'd line them up and cut them down from one end to the other."[3]References

[edit]- ^ Wakabayashi 2000, p. 319.

- ^ Kajimoto 2015, p. 37, Postwar Judgment: II. Nanking War Crimes Tribunal.

- ^ Honda 1999, pp. 125–127.

Sources

[edit]- Honda, Katsuichi (1999) [Main text from Nankin e no Michi (The Road to Nanjing), 1987.], Gibney, Frank (ed.), The Nanjing Massacre: A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan's National Shame, M. E. Sharpe, ISBN 0-7656-0335-7, retrieved 24 February 2010

- Kajimoto, Masato (July 2015), The Nanking Massacre: Nanking War Crimes Tribunal, Graduate School of Journalism of the University of Missouri-Columbia, 172, archived from the original on 13 July 2015, retrieved 4 August 2016,

However, as many historians point out today, the stories of hyped heroism, in which those soldiers courageously killed a number of enemies in hand-to-hand combat with swords, couldn't be taken at face value. ... The three researchers interviewed by author for this project, Daqing Yang, Ikuhiko Hata, and Akira Fujiwara said that the contest could have been mere mass murder of prisoners.

- Wakabayashi, Bob Tadashi (Summer 2000), "The Nanking 100-Man Killing Contest Debate: War Guilt Amid Fabricated Illusions, 1971–75", Journal of Japanese Studies, 26 (2), The Society for Japanese Studies: 307–340, doi:10.2307/133271, ISSN 0095-6848, JSTOR 133271

Further reading

[edit]- De Lange, William (2023). A History of Japanese Journalism: State of Affairs and Affairs of State. Toyo Press. ISBN 978-94-92722-393.