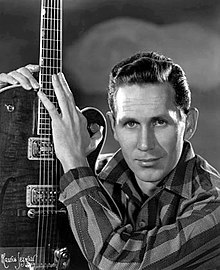

Chet Atkins

Chet Atkins | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Chester Burton Atkins |

| Also known as | "Mister Guitar", "The Country Gentleman" |

| Born | June 20, 1924 Luttrell, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | June 30, 2001 (aged 77) Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instrument | Guitar |

| Discography | Chet Atkins discography |

| Years active | 1942–1996 |

| Labels | RCA Victor, Columbia |

| Formerly of |

|

| Website | misterguitar |

Chester Burton Atkins (June 20, 1924 – June 30, 2001), also known as "Mister Guitar" and "the Country Gentleman", was an American musician who, along with Owen Bradley and Bob Ferguson, helped create the Nashville sound, the country music style which expanded its appeal to adult pop music fans. He was primarily a guitarist, but he also played the mandolin, fiddle, banjo, and ukulele, and occasionally sang.

Atkins's signature picking style was inspired by Merle Travis. Other major guitar influences were Django Reinhardt, George Barnes, Les Paul, and, later, Jerry Reed.[1] His distinctive picking style and musicianship brought him admirers inside and outside the country scene, both in the United States and abroad. Atkins spent most of his career at RCA Victor and produced records for the Browns, Hank Snow, Porter Wagoner, Norma Jean, Dolly Parton, Dottie West, Perry Como, Floyd Cramer, Elvis Presley, the Everly Brothers, Eddy Arnold, Don Gibson, Jim Reeves, Jerry Reed, Skeeter Davis, Waylon Jennings, Roger Whittaker, Ann-Margret and many others.

Rolling Stone credited Atkins with inventing the "popwise 'Nashville sound' that rescued country music from a commercial slump" and ranked him number 21 on their list of "The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time".[2] In 2023, Atkins was named the 39th best guitarist of all time.[3] Among many other honors, Atkins received 14 Grammy Awards and the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. He also received nine Country Music Association awards for Instrumentalist of the Year. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, and the Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum. George Harrison was also inspired by Chet Atkins; early Beatles songs such as "All My Loving" show the influence.

Biography

[edit]Childhood and early life

[edit]Atkins was born on June 20, 1924, in Luttrell, Tennessee, near Clinch Mountain. His parents divorced when he was six years old, after which he was raised by his mother. He was the youngest of three boys and a girl. He started out on the ukulele, later moving on to the fiddle, but he made a swap with his brother Lowell when he was nine: an old pistol and some chores for a guitar.[4] He stated in his 1974 autobiography, "We were so poor and everybody around us was so poor that it was the forties before anyone even knew there had been a depression." Forced to relocate to Fortson, Georgia, outside of Columbus to live with his father because of a critical asthma condition, Atkins was a sensitive youth who became obsessed with music. Because of his illness, he was forced to sleep in a straight-back chair to breathe comfortably. On those nights, he played his guitar until he fell asleep holding it, a habit that lasted his whole life.[5] While living in Fortson, Atkins attended the historic[citation needed] Mountain Hill School. He returned in the 1990s to play a series of charity concerts to save the school from demolition.[6] Stories have been told about the very young Chet who, when a friend or relative would come to visit and play guitar, crowded the musician and put his ear so close to the instrument that it became difficult for the visitor to play.[5]

Atkins became an accomplished guitarist while he was in high school.[4] He used the restroom in the school to practice because it had good acoustics.[7][8] His first guitar had a nail for a nut and was so bowed that only the first few frets could be used.[9] He later purchased a semi-acoustic electric guitar and amp, but he had to travel many miles to find an electrical outlet, since his home didn't have electricity.[10]

Later in life, he lightheartedly gave himself (along with John Knowles, Tommy Emmanuel, Steve Wariner, and Jerry Reed[11]) the honorary degree CGP ("Certified Guitar Player").[9] In 2011, his daughter Merle Atkins Russell bestowed the CGP degree on his longtime sideman Paul Yandell. She then declared no more CGPs would be allowed by the Atkins estate.[12]

His half-brother Jim was a successful guitarist who worked with the Les Paul Trio in New York.[5]

Atkins did not have a strong style of his own until 1939 when (while still living in Georgia) he heard Merle Travis picking over WLW radio.[5][13] This early influence dramatically shaped his unique playing style.[1] Whereas Travis used his index finger on his right hand for the melody and his thumb for the bass notes, Atkins expanded his right-hand style to include picking with his first three fingers, with the thumb on bass. He also listened closely to the single-string playing of George Barnes and Les Paul.

Chet Atkins was an amateur radio general class licensee. Formerly using the call sign WA4CZD, he obtained the vanity call sign W4CGP in 1998 to include the CGP designation, which supposedly stood for "Certified Guitar Picker". He was a member of the American Radio Relay League.[14]

Early musical career

[edit]After dropping out of high school in 1942, Atkins landed a job at WNOX (AM) (now WNML) radio in Knoxville, where he played fiddle and guitar with the singer Bill Carlisle and the comic Archie Campbell and became a member of the station's Dixieland Swingsters, a small swing instrumental combo. After three years, he moved to WLW-AM in Cincinnati, Ohio, where Merle Travis had formerly worked.

After six months, he moved to Raleigh and worked with Johnnie and Jack before heading for Richmond, Virginia, where he performed with Sunshine Sue Workman. Atkins's shy personality worked against him, as did the fact that his sophisticated style led many to doubt he was truly "country". He was fired often but was soon able to land another job at another radio station on account of his unique playing ability.[5]

Atkins and Jethro Burns (of Homer and Jethro) married twin sisters Leona and Lois Johnson, who sang as Laverne and Fern Johnson, the Johnson Sisters. Leona Atkins outlived her husband by eight years, dying in 2009 at the age of 85.[15]

Travelling to Chicago, Atkins auditioned for Red Foley, who was leaving his star position on WLS-AM's National Barn Dance to join the Grand Ole Opry.[16] Atkins made his first appearance at the Opry in 1946 as a member of Foley's band. He also recorded a single for Nashville-based Bullet Records that year. That single, "Guitar Blues", was fairly progressive, including a clarinet solo by the Nashville dance band musician Dutch McMillan and produced by Owen Bradley. He had a solo spot on the Opry, but when that was cut, Atkins moved on to KWTO in Springfield, Missouri. Despite the support of executive Si Siman, however, he soon was fired for not sounding "country enough".[5]

Signing with RCA Victor

[edit]While working with a Western band in Denver, Colorado, Atkins came to the attention of RCA Victor. Siman had been encouraging Steve Sholes to sign Atkins, as his style (with the success of Merle Travis as a hit recording artist) was suddenly in vogue. Sholes, A&R director of country music at RCA, tracked Atkins down in Denver.

He made his first RCA Victor recordings in Chicago in 1947, but they did not sell. He did some studio work for RCA that year, but had relocated to Knoxville again where he worked with Homer and Jethro on WNOX's new Saturday night radio show The Tennessee Barn Dance and the popular Midday Merry Go Round.

In 1949, he left WNOX to join June Carter with Mother Maybelle and the Carter Sisters on KWTO. This incarnation of the Carter Family featured Maybelle Carter and daughters June, Helen, and Anita. Their work soon attracted attention from the Grand Ole Opry. The group relocated to Nashville in the mid-1950s. Atkins began working on recording sessions and performing on WSM-AM and the Opry.[5] Atkins became a member of the Opry in the 1950s.[17]

While he had not yet had a hit record for RCA Victor, his stature was growing. He began assisting Sholes as a session leader when the New York–based producer needed help organizing Nashville sessions for RCA Victor artists. Atkins's first hit single was "Mr. Sandman", followed by "Silver Bell", which he recorded as a duet with Hank Snow. His albums also became more popular. He was featured on ABC-TV's The Eddy Arnold Show in the summer of 1956 and on Country Music Jubilee in 1957 and 1958 (by then renamed Jubilee USA).

In addition to recording, Atkins was a design consultant for Gretsch, which manufactured a popular Chet Atkins line of electric guitars from 1955 to 1980. He became manager of RCA Victor's Nashville studios, eventually inspiring and seeing the completion of the legendary RCA Studio B, the first studio built specifically for the purpose of recording on the now-famous Music Row. Also later on, Chet and Owen Bradley would become instrumental in the creation of studio B's adjacent building RCA Studio A as well.[9]

Performer and producer

[edit]When Sholes took over pop production in 1957—a result of his success with Elvis Presley—he put Atkins in charge of RCA Victor's Nashville division. With country music record sales declining as rock and roll became more popular, Atkins took his cue from Owen Bradley and eliminated fiddles and steel guitar from many recordings, though not all, as a means of making country singers appeal to pop fans, many of whom disliked the "twang" elements of country. This became known as the Nashville Sound, which Atkins said was a label created by the media for a style of recording during that period intended to keep country (and their jobs) viable.

Atkins used the Jordanaires and a rhythm section on hits such as Jim Reeves's "Four Walls" and "He'll Have to Go"[18] and Don Gibson's "Oh Lonesome Me" and "Blue Blue Day".[19] The once-rare phenomenon of having a country hit cross over to pop success became more common. He and Bradley had essentially put the producer in the driver's seat, guiding an artist's choice of material and the musical background. Other Nashville producers quickly copied this successful formula, which resulted in certain country hits "crossing over" to find success in the pop field.

Atkins made his own records, which usually visited pop standards and jazz, in a sophisticated home studio, often recording the rhythm tracks at RCA and adding his solo parts at home, refining the tracks until the results satisfied him.[9] Guitarists of all styles came to admire various Atkins albums for their unique musical ideas and in some cases experimental electronic ideas. In this period, he became known internationally as "Mister Guitar", inspiring an album, Mister Guitar, engineered by both Bob Ferris and Bill Porter, Ferris's replacement.

At the end of March 1959, Porter took over as chief engineer at what was at the time RCA Victor's only Nashville studio, in the space that would become known as Studio B after the opening of a second studio in 1965. (At the time, RCA's sole Nashville studio had no letter designation.) Porter soon helped Atkins get a better reverberation sound from the studio's German effects device, an EMT plate reverb. With his golden ear, Porter found the studio's acoustics to be problematic, and he devised a set of acoustic baffles to hang from the ceiling, then selected positions for microphones based on resonant room modes. The sound of the recordings improved significantly, and the studio achieved a string of successes. The Nashville sound became more dynamic.[20] In later years, when Bradley asked how he achieved his sound, Atkins told him "it was Porter."[21] Porter described Atkins as respectful of musicians when recording—if someone was out of tune, he would not single that person out by name. Instead, he would say something like, "we got a little tuning problem ... Everybody check and see what's going on."[21] If that did not work, Atkins would instruct Porter to turn the offending player down in the mix. When Porter left RCA in late-1964, Atkins said, "the sound was never the same, never as great."[21]

Atkins's trademark "Atkins style" of playing uses the thumb and first two or sometimes three fingers of the right hand. He developed this style from listening to Merle Travis,[1] occasionally on a primitive radio. He was sure no one could play that articulately with just the thumb and index finger (which was exactly how Travis played), and he assumed it required the thumb and two fingers—and that was the style he pioneered and mastered.

He enjoyed jamming with fellow studio musicians, and they were asked to perform at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960. That performance was cancelled because of rioting, but a live recording of the group (After the Riot at Newport) was released. Atkins performed by invitation at the White House for every U.S. president from John F. Kennedy through to George H. W. Bush. Atkins was a member of the Million Dollar Band during the 1980s. He is also well known for his song "Yankee Doodle Dixie", in which he played "Yankee Doodle" and "Dixie" simultaneously, on the same guitar.

Before his mentor Sholes died in 1968, Atkins had become vice president of RCA's country division. In 1987, he told Nine-O-One Network magazine that he was "ashamed" of his promotion: "I wanted to be known as a guitarist and I know, too, that they give you titles like that in lieu of money. So beware when they want to make you vice president."[22] He had brought Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Connie Smith, Bobby Bare, Dolly Parton, Jerry Reed, and John Hartford to the label in the 1960s and inspired and helped countless others.[23] He took a considerable risk during the mid-1960s, when the civil rights movement sparked violence throughout the South, by signing country music's first African-American singer, Charley Pride, who sang rawer country than the smoother music Atkins had pioneered.

Atkins's biggest hit single came in 1965, with "Yakety Axe", an adaptation of "Yakety Sax", by his friend, the saxophonist Boots Randolph. He rarely performed in those days and eventually hired other RCA producers, such as Bob Ferguson and Felton Jarvis, to lessen his workload.[9]

Later career

[edit]In the 1970s, Atkins became increasingly stressed by his executive duties. He produced fewer records, but could still turn out hits such as Perry Como's 1973 pop hit "And I Love You So". He recorded extensively with close friend and fellow picker Jerry Reed, who had become a hit artist in his own right. A 1973 diagnosis of colon cancer, however, led Atkins to redefine his role at RCA Records, to allow others to handle administration while he went back to his first love, the guitar, often recording with Reed or even Jethro Burns from Homer and Jethro (his brother-in-law) after Homer died in 1971.[9] Atkins would turn over his administrative duties to Jerry Bradley, son of Owen, in 1973 at RCA.

Atkins did little production work at RCA after stepping down and in fact, had hired producers at the label in the 1960s, among them Bob Ferguson and Felton Jarvis. As a recording artist, Atkins grew disillusioned with RCA in the late 1970s. He felt stifled because the record company would not let him branch into jazz. He had also produced late '60s jazz recordings by Canadian guitarist Lenny Breau, a friend and protege. His mid-1970s collaborations with one of his influences, Les Paul, Chester & Lester and Guitar Monsters, had already reflected that interest; Chester & Lester was one of the best-selling recordings of Atkins's career. At the same time, he grew dissatisfied with the direction Gretsch (no longer family-owned) was going and withdrew his authorization for them to use his name and began designing guitars with Gibson. In 1982, Atkins ended his 35-year association with RCA Records and signed with rival Columbia Records. He produced his first album for Columbia in 1983.[16]

Atkins had always been an ardent lover of jazz and throughout his career he was often criticized by "pure" country musicians for his jazz influences. He also said on many occasions that he did not like being referred to as a "country guitarist", insisting that he was "a guitarist, period." Although he played by ear and was a masterful improviser, he was able to read music and even performed some classical guitar pieces. When Roger C. Field, a friend, suggested to him in 1991 that he record and perform with a female singer, he did so with Suzy Bogguss.[9]

Atkins returned to his country roots for albums he recorded with Mark Knopfler and Jerry Reed.[9] Knopfler had long mentioned Atkins as one of his earliest influences. Atkins also collaborated with Australian guitar legend Tommy Emmanuel. On being asked to name the ten most influential guitarists of the twentieth century, he named Django Reinhardt to the first position, and also placed himself on the list.[24]

In later years, he returned to radio, appearing on Garrison Keillor's Prairie Home Companion program, on American Public Media radio, even picking up a fiddle from time to time,[9] and performing songs such as Bob Wills's "Corrina, Corrina" and Willie Nelson's "Seven Spanish Angels" with Nelson on a 1985 broadcast of the show at the Bridges Auditorium on the campus of Pomona College.

Death and legacy

[edit]Atkins received numerous awards, including 14 Grammy awards and nine Country Music Association awards for Instrumentalist of the Year.[16] In 1993, he was honored with the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. Billboard magazine awarded him its Century Award, its "highest honor for distinguished creative achievement", in December 1997.[25] In 2002, Atkins was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[23] His award was presented by Marty Stuart and Brian Setzer and accepted by Atkins's grandson, Jonathan Russell. The following year, Atkins ranked number 28 in Country Music Television's "40 Greatest Men of Country Music". In November 2011, Rolling Stone ranked Atkins number 21 on their list of the "100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time".[2]

Atkins is notable for his broad influence. His love for numerous styles of music can be traced from his early recording of the stride pianist James P. Johnson's "Johnson Rag", all the way to the rock stylings of Eric Johnson, an invited guest on Atkins's recording sessions, who, when Atkins attempted to copy his influential rocker "Cliffs of Dover", led to Atkins's creation of a unique arrangement of "Londonderry Air (Danny Boy)".

The classical guitar selections included on almost all his albums were, for many American artists working in the field today, the first classical guitar they ever heard. He recorded smooth jazz guitar still played on American airwaves.

Atkins continued performing in the 1990s, but his health declined after he was again diagnosed with colon cancer in 1996. He died on June 30, 2001, at his home in Nashville, Tennessee, at age 77.[26] His memorial service was held at Ryman Auditorium in Nashville.[27] He was buried at Harpeth Hills Memory Gardens in Nashville.

A stretch of Interstate 185 in southwest Georgia (between LaGrange and Columbus) is named "Chet Atkins Parkway".[28] This stretch of interstate runs through Fortson, where Atkins spent much of his childhood.

At the age of 13, the future jazz guitarist Earl Klugh was captivated watching Atkins perform on The Perry Como Show.[29] He was also a big influence on Doyle Dykes,[30] and inspired Tommy Emmanuel.[31] Johnny Winter's thumb-picking style came from Atkins' playing.[32] Steve Howe called Atkins his favorite "all round guitarist", adding that "there are those in different areas of music who are better than him, but nobody had the same ability when it comes to being across the board. For me, it was an education to listen to what he did."[33]

Clint Black's album Nothin' but the Taillights includes the song "Ode to Chet", which includes the lyrics "'Cause I can win her over like Romeo did Juliet, if I can only show her I can almost pick that legato lick like Chet" and "It'll take more than Mel Bay 1, 2, & 3 if I'm ever gonna play like CGP." Atkins played guitar on the track. At the end of the song, Black and Atkins had a brief conversation.

Atkins' song "Jam Man" is currently[when?] used in commercials for Esurance.

In 1967, a tribute song, "Chet's Tune", was produced for Atkins' birthday, with contributions by a long list of RCA Victor artists, including Eddy Arnold, Connie Smith, Jerry Reed, Willie Nelson, Hank Snow, and others. The song was written by the Nashville songwriter Cy Coben, a friend of Atkins. The single reached number 38 on the country charts.[34][35][36]

In 2009, Steve Wariner released an album titled My Tribute to Chet Atkins. One song from that record, "Producer's Medley", featured Wariner's recreation of several famous songs that Atkins both produced and performed. "Producer's Medley" won the Grammy for Best Country Instrumental Performance in 2010.

Discography

[edit]Industry awards

[edit]- 1967 Instrumentalist of the Year

- 1968 Instrumentalist of the Year

- 1969 Instrumentalist of the Year

- 1981 Instrumentalist of the Year

- 1982 Instrumentalist of the Year

- 1983 Instrumentalist of the Year

- 1984 Instrumentalist of the Year

- 1985 Instrumentalist of the Year

- 1988 Musician of the Year

Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

| Award | Year | Work/s | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 Best Country Instrumental Performance with Jerry Reed – | 1972 | Me and Jerry | Won |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance | 1972 | "Snowbird" | Won |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance with Merle Travis – | 1973 | The Atkins-Travis Traveling Show | Won |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance | 1976 | "The Entertainer" | Won |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance with Les Paul | 1977 | Chester and Lester | Won |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance | 1982 | Country After All These Years | Won |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance with Mark Knopfler | 1986 | "Cosmic Square Dance" | Won |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance with Mark Knopfler | 1991 | "So Soft, Your Goodbye" | Won |

| 1991 Best Country Vocal Collaboration with Mark Knopfler | 1991 | "Poor Boy Blues" | Won |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance with Jerry Reed | 1993 | Sneakin' Around | Won |

| 1993 Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award' | 1993 | Honoured | |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance with Asleep at the Wheel, Eldon Shamblin, Johnny Gimble, Marty Stuart, Reuben "Lucky Oceans" Gosfield & Vince Gill | 1994 | "Red Wing" | Won |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance | 1995 | "Young Thing" | Won |

| Best Country Instrumental Performance | 1996 | "Jam Man" | Won |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 10 – Tennessee Firebird: American Country Music Before and After Elvis. [Part 2]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- ^ a b "Chet Atkins" Archived August 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone.

- ^ "The 250 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". Rolling Stone. October 13, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ a b "Country Music Television biography". CMT. Archived from the original on January 10, 2004. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Atkins, Chet; Neely, Bill (1974). "Country Gentleman." Chicago. Harry Regnery. ISBN 0-8092-9051-0.

- ^ Rush, Dianne Samms (October 23, 1994). "Chet Plays; Gatlin Lives". Lakeland Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. p. 9C. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ Atkins, Chet; Neely, Bill (1974). "Country Gentleman". Chicago. Harry Regnery. p. 52. ISBN 0-8092-9051-0.

- ^ Halberstam, David (1961). liner notes. Chet Atkins' Workshop. RCA Victor LSP-2232.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Atkins, Chet; Cochran, Russ (2003). "Me and My Guitars." Milwaukee: Hal Leonard. ISBN 0-634-05565-8.

- ^ Atkins, Chet; Neely, Bill. (1974). "Country Gentleman." Chicago. Harry Regnery. pp. 61–62. ISBN 0-8092-9051-0.

- ^ 'Interview of Chet Atkins' on YouTube

- ^ Freeman, Jon (November 22, 2011). "A Guitarist Paul Yandell Passes". Music Row. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ *Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum Archived October 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "American Radio Relay League | Ham Radio Association and Resources". Arrl.org. Archived from the original on September 20, 2005.

- ^ "Chet Atkins' Widow Dies". Country Standard Time. October 22, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Chet Atkins Dies"[dead link] Rolling Stone. Accessed on March 28, 2008.

- ^ "Opry Timeline – 1950s". Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- ^ Allmusic entry for Welcome to My World, Jim Reeves 1996 box set, Bear Family Records

- ^ Allmusic biography of Don Gibson

- ^ Ballou, Glen (1998). Handbook for Sound Engineers. Focal Press. p. 1154.

- ^ a b c McClellan, John; Bratic, Deyan (2004). Chet Atkins in Three Dimensions. Vol. 2. Mel Bay Publications. pp. 149–152. ISBN 978-0-7866-5877-0.

- ^ Nine-O-One Interview, Nine-O-One Network Magazine, December 1987, p.10-11

- ^ a b "Chet Atkins", Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Accessed on March 28, 2008.

- ^ Official Web Site of Chet Atkins. Accessed on August 27, 2014.

- ^ "Biography – Chet Atkins". Rolling Stone. Accessed on May 10, 2008.

- ^ "Obituary" Archived March 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, CNN, July 2, 2001 Accessed June 21, 2008

- ^ "Guitars Gently Weep as Nashville Pays Tribute to Chet Atkins". The New York Times. July 4, 2001. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ "Chet Atkins Parkway Bill Resolution". Archived from the original on January 28, 2005. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ "Performing Arts Center, Buffalo State University". Buffalo State. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ^ Turner, Dale (June 18, 2014). "Acoustic Nation with Dale Turner: The Guitar Gospel of Brilliant Fingerstylist Doyle Dykes". Guitar World. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ Tommy Emmanuel official website biography. Archived August 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved September 2009.

- ^ "Johnny Winter Interview: April 2004". Andyaledort.com. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ Dome, Malcolm (April 8, 2020). "Steve Howe: The 10 Records That Changed My Life". Louder. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ Billboard, June 3, 1967, p. 41.

- ^ McClellan, John; Bratic, Deyan. Chet Atkins in Three Dimensions: 50 Years of Legendary Guitar, vol. 1. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay Publications. pp. 47–49.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2008). Hot Country Songs 1944 to 2008. Record Research. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-89820-177-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Kienzle, Rich (1998). "Chet Atkins". The Encyclopedia of Country Music. Paul Kingsbury, ed. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 26–27.

External links

[edit]- 1924 births

- 2001 deaths

- 20th-century American singer-songwriters

- 20th-century classical musicians

- Amateur radio people

- American country guitarists

- American country singer-songwriters

- American male guitarists

- American music industry executives

- Record producers from Tennessee

- Deaths from cancer in Tennessee

- Deaths from colorectal cancer in the United States

- Columbia Records artists

- Country Music Hall of Fame inductees

- Country musicians from Tennessee

- American fingerstyle guitarists

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Grand Ole Opry members

- Million Dollar Band (country music group) members

- Music of East Tennessee

- Musicians from Appalachia

- Singer-songwriters from Tennessee

- Musicians from Knoxville, Tennessee

- People from Union County, Tennessee

- RCA Records Nashville artists

- RCA Victor artists

- 20th-century American guitarists

- Guitarists from Tennessee

- 20th-century American male musicians

- American male singer-songwriters