Peanuts

| Peanuts | |

|---|---|

The Peanuts gang Top row left to right: Woodstock, Snoopy, Charlie Brown Bottom row left to right: Franklin, Lucy Van Pelt, Linus Van Pelt, Peppermint Patty, Sally Brown | |

| Author(s) | Charles M. Schulz |

| Website | www |

| Current status/schedule | Concluded, in reruns |

| Launch date |

|

| End date |

|

| Syndicate(s) |

|

| Genre(s) | Humor, gag-a-day, satire, children |

Peanuts is a syndicated daily and Sunday American comic strip written and illustrated by Charles M. Schulz. The strip's original run extended from 1950 to 2000, continuing in reruns afterward. Peanuts is among the most popular and influential in the history of comic strips, with 17,897 strips published in all,[1] making it "arguably the longest story ever told by one human being".[2] At the time of Schulz's death in 2000, Peanuts ran in over 2,600 newspapers, with a readership of roughly 355 million across 75 countries, and had been translated into 21 languages.[3] It helped to cement the four-panel gag strip as the standard in the United States,[4] and together with its merchandise earned Schulz more than $1 billion.[1] It got a movie adaptation in 2015 by Blue Sky Studios.[5]

Peanuts focuses on a social circle of young children, where adults exist but are rarely seen or heard. The main character, Charlie Brown, is meek, nervous, and lacks self-confidence. He is unable to fly a kite, win a baseball game, or kick a football held by his irascible friend Lucy, who always pulls it away at the last instant.[6] Peanuts is a literate strip with philosophical, psychological, and sociological overtones, which was innovative in the 1950s.[7] Its humor is psychologically complex and driven by the characters' interactions and relationships. The comic strip has been adapted in animation and theater.

Schulz drew the strip for nearly 50 years, with no assistants, even in the lettering and coloring process.[8]

Title

[edit]Peanuts was originally sold under the title of Li'l Folks, but that had been used before, so they said we have to think of another title. I couldn't think of one and somebody at United Features came up with the miserable title Peanuts, which I hate and have always hated. It has no dignity and it's not descriptive. [...] What could I do? Here I was, an unknown kid from St. Paul. I couldn't think of anything else. I said, why don't we call it Charlie Brown and the president said "Well, we can't copyright a name like that." I didn't ask them about Nancy or Steve Canyon. I was in no position to argue.

—Charles Schulz, in a 1987 interview with Frank Pauer in Dayton Daily News and Journal Herald Magazine[9]

Peanuts had its origin in Li'l Folks, a weekly panel cartoon that appeared in Schulz's hometown newspaper, the St. Paul Pioneer Press, from 1947 to 1950. Elementary details of the cartoon shared similarities to Peanuts. The name "Charlie Brown" was first used there. The series also had a dog that looked much like the early 1950s version of Snoopy.[10]

Schulz submitted his Li'l Folks cartoons to United Features Syndicate (UFS), who responded with interest. He visited the syndicate in New York City and presented a package of new comic strips he had worked on, rather than the panel cartoons he submitted. UFS found they preferred the comic strip.[9][11] When UFS was preparing to syndicate the comic strip as Li'l Folk, Tack Knight, who authored the retired 1930s comic strip Little Folks, sought to claim exclusive rights to the title being used. Schulz argued in a letter to Knight that the contraction of Little to Li'l was intended to avoid this conflict, but conceded that the final decision would be for the syndicate. A different name for the comic strip became necessary after legal advice confirmed that Little Folks was a registered trademark.[12] Meanwhile, the production manager of UFS noted the popularity of the children's program Howdy Doody. The show featured an audience of children who were seated in the "Peanut Gallery", and were referred to as "Peanuts". This inspired the decided title that was forced upon Schulz, to his consternation.[13]

Schulz hated the title Peanuts, which remained a source of irritation to him throughout his life. He accused the production manager at UFS of not having even seen the comic strip before giving it a title, and he said that the title would only make sense if there was a character named "Peanuts".[14] On the day it was syndicated, Schulz's friend visited a news stand in uptown Minneapolis and asked if there were any newspapers that carried Peanuts, to which the newsdealer replied, "No, and we don't have any with popcorn either", which confirmed Schulz's fears concerning the title.[15] Whenever Schulz was asked what he did for a living, he would evade mentioning the title and say, "I draw that comic strip with Snoopy in it, Charlie Brown and his dog".[16] In 1997 Schulz said that he had discussed changing the title to Charlie Brown on multiple occasions in the past but found that it would ultimately cause problems with licensees who already incorporated the existing title into their products, with unnecessary expenses involved for all downstream licensees to change it.[17]

History

[edit]1950s

[edit]

The strip began as a daily strip on October 2, 1950, in seven newspapers: the Minneapolis Star, a hometown newspaper of Schulz (page 37, along with a short article); The Washington Post; Chicago Tribune; The Denver Post; The Seattle Times; and two newspapers in Pennsylvania, Evening Chronicle (Allentown) and Globe-Times (Bethlehem).[18] The first strip was four panels long and showed Charlie Brown walking by two other young children, Shermy and Patty. Shermy lauds Charlie Brown as he walks by, but then tells Patty how he hates him in the final panel. Snoopy was also an early character in the strip, first appearing in the third strip, which ran on October 4.[19] Its first Sunday strip appeared January 6, 1952, in the half-page format, which was the only complete format for the entire life of the Sunday strip. Most of the other characters that eventually became regulars of the strip did not appear until later: Violet (February 1951), Schroeder (May 1951), Lucy (March 1952), Linus (September 1952), Pig-Pen (July 1954), Sally (August 1959), Frieda (March 1961), "Peppermint" Patty (August 1966), Franklin (July 1968), Woodstock (introduced March 1966, officially named June 1970), Marcie (July 1971), and Rerun (March 1973).

Schulz decided to produce all aspects of the strip himself from the script to the finished art and lettering. Schulz did, however, hire help to produce the comic book adaptations of Peanuts.[20] Thus, the strip was able to be presented with a unified tone, and Schulz was able to employ a minimalistic style. Backgrounds were generally not used, and when they were, Schulz's frazzled lines imbued them with a fraught, psychological appearance. This style has been described by art critic John Carlin as forcing "its readers to focus on subtle nuances rather than broad actions or sharp transitions."[21] Schulz held this belief all his life, reaffirming in 1994 the importance of crafting the strip himself: "This is not a crazy business about slinging ink. This is a deadly serious business."[22]

While the strip in its early years resembles its later form, there are significant differences. The art was cleaner, sleeker, and simpler, with thicker lines and short, squat characters. For example, in these early strips, Charlie Brown's famous round head is closer to the shape of an American football or rugby football. Most of the kids were initially fairly round-headed. As another example, all the characters (except Charlie Brown) had their mouths longer and had smaller eyes when they looked sideways.

1960s

[edit]The 1960s is generally considered to be the "golden age" for Peanuts.[23] During this period, some of the strip's best-known themes and characters appeared, including Peppermint Patty,[24] Snoopy as the "World War One Flying Ace",[25] Frieda and her "naturally curly hair",[26] and Franklin.[27] Peanuts is remarkable for its deft social commentary, especially compared with other strips appearing in the 1950s and early 1960s. Schulz did not explicitly address racial and gender equality issues so much as assume them to be self-evident. Peppermint Patty's athletic skill and self-confidence are simply taken for granted, for example, as is Franklin's presence in a racially integrated school and neighborhood. (Franklin's creation occurred at least in part as a result of Schulz's 1968 correspondence with a socially progressive fan.[28][29]) The fact that Charlie Brown's baseball team had three girls on it was also at least ten years ahead of its time. The 1966 prime time television special Charlie Brown's All Stars! dealt with Charlie Brown refusing sponsorship of his team on the condition he fire the girls and Snoopy, because the league does not allow girls or dogs to play.

Schulz threw satirical barbs at any number of topics when he chose. His child and animal characters satirized the adult world.[30] Over the years he tackled everything from the Vietnam War to school dress codes to "New Math". The May 20, 1962 strip featured an icon that stated "Defend Freedom, Buy U.S. Savings Bonds."[31] In 1963 he added a little boy named "5" to the cast,[32] whose sisters were named "3" and "4,"[33] and whose father had changed their family name to their ZIP Code, giving in to the way numbers were taking over people's identities. Also in 1963, one strip showed Sally being secretive about school prayer, in reference to the Supreme Court decisions on it that year.[34] In 1958, a strip in which Snoopy tossed Linus into the air and boasted that he was the first dog ever to launch a human parodied the hype associated with Sputnik 2's launch of Laika the dog into space earlier that year. Another sequence lampooned Little Leagues and "organized" play when all the neighborhood kids join snowman-building leagues and criticize Charlie Brown when he insists on building his own snowmen without leagues or coaches.

Peanuts touched on religious themes on many occasions, especially during the 1960s. The classic television special A Charlie Brown Christmas from 1965, features the character Linus van Pelt quoting the King James Version of the Bible (Luke 2:8–14) to explain to Charlie Brown what Christmas is all about (in personal interviews, Schulz mentioned that Linus represented his spiritual side). Because of the explicit religious material in A Charlie Brown Christmas, many have interpreted Schulz's work as having a distinct Christian theme, though the popular perspective has been to view the franchise through a secular lens.[35]

During the week of July 29, 1968, Schulz debuted the African American character Franklin to the strip, at the urging of white Jewish Los Angeles schoolteacher Harriet Glickman. Though Schulz feared that adding a black character would be seen as patronizing to the African American community, Glickman convinced him that the addition of Black characters could help normalize the idea of friendships between children of different ethnicities. Franklin appeared in a trio of strips set at a beach, in which he first gets Charlie Brown's beach ball from the water and subsequently helps him build a sand castle, during which he mentions that his father is in Vietnam.

1970s–1990s

[edit]In 1975, the panel format was shortened slightly horizontally, and shortly thereafter the lettering became larger to compensate. Previously, the daily Peanuts strips were formatted in a four-panel "space saving" format beginning in the 1950s, with a few very rare eight-panel strips, that still fit into the four-panel mold. Beginning on Leap Day in 1988, Schulz abandoned the four-panel format in favor of three-panel dailies and occasionally used the entire length of the strip as one panel, partly for experimentation, but also to combat the dwindling size of the comics page.[citation needed]

In the late 1970s, during Schulz's negotiations with United Feature Syndicate over a new contract, syndicate president William C. Payette hired superhero comic artist Al Plastino to draw a backlog of Peanuts strips to hold in reserve in case Schulz left the strip. When Schulz and the syndicate reached a successful agreement, United Media stored these unpublished strips, the existence of which eventually became public.[36] Plastino himself also claimed to have ghostwritten for Schulz while Schulz underwent heart surgery in 1983.[37]

In the 1980s and the 1990s, the strip remained the most popular comic in history,[38] even though other comics, such as Garfield and Calvin and Hobbes, rivaled Peanuts in popularity. Schulz continued to write the strip until announcing his retirement on December 14, 1999, due to his failing health.

2000: End of Peanuts

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

The last three Peanuts strips were run from Saturday, January 1, 2000, through Monday, January 3, 2000. The Saturday strip showed a snowball fight between Peppermint Patty and Marcie and Charlie Brown and Linus, with Snoopy sitting behind the fight trying to figure out how to throw a snowball. The strip was notable because, in addition to it being the last daily strip with a story, Schulz's health had deteriorated to the point where the lettering in the strip had to be done by computer.

The Sunday strip featured the last appearances of Peppermint Patty and Marcie, with Peppermint Patty playing a game of football in the rain by herself. Marcie comes up, carrying an umbrella and remarking that everyone has gone home. Peppermint Patty laments that they never shook hands and said "good game".[39]

The January 3 strip consisted of a drawing of Snoopy sitting atop his doghouse with his typewriter, as he had done many times over the course of the strip's lifespan. The drawing was accompanied by a printed note from Schulz which officially announced his retirement from drawing and thanking his readers for their support.

Although a series of reruns of older strips would begin on January 4, 2000, there were still six unpublished Sunday strips that Schulz had completed. The first of these ran on January 9, featuring Rerun and Snoopy playing in the snow.[40] The second featured the last appearance of Woodstock, as he and Snoopy in one last fantasy sequence are called upon by George Washington to chop firewood.[41] Rerun makes his final appearance in the fourth, trying to paint something other than flowers in art class, and Sally makes her last appearance in the fifth conversing with Charlie Brown about love letters.

The final Peanuts strip, as shown here, ran on February 13, 2000, the night after Schulz died from a heart attack. It consisted of two small panels across the top and a large panel at the bottom. The title panel shows Charlie Brown talking to someone on the telephone, who is apparently asking to speak to Snoopy. Charlie Brown responds by telling the caller "no, I think he’s writing". The second panel shows Snoopy sitting atop his doghouse typing on his typewriter as he had many times before, while the words "Dear Friends…" appeared above his head.

The larger panel at the bottom consisted of a larger scale drawing of the final daily strip, with Snoopy against a blue sky background. Above his head, several panels from past strips were overlaid. Underneath these panels, the full note that Schulz had written to his fans was printed (part of it had been omitted in the final daily strip). It read as follows:

Dear Friends,

I have been fortunate to draw Charlie Brown and his friends for almost fifty years. It has been the fulfillment of my childhood ambition.

Unfortunately, I am no longer able to maintain the schedule demanded by a daily comic strip. My family does not wish "Peanuts" to be continued by anyone else, therefore I am announcing my retirement.

I have been grateful over the years for the loyalty of our editors and the wonderful support and love expressed to me by fans of the comic strip.

Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy, …how can I ever forget them…

— Charles M. Schulz

Many other cartoonists paid tribute to Peanuts and Schulz by homages in their own strips, appearing on February 13, 2000, or in the week beforehand.[42] The comic was reprinted the day after that, but only had the farewell letter. After Peanuts ended, United Feature Syndicate began offering the newspapers that ran it a package of reprinted strips under the title Classic Peanuts. The syndicate limited the choices to either strips from the 1960s or from the 1990s, although a newspaper was also given the option to carry both reprint packages if it desired. All Sunday strips in the package, however, come from the 1960s.

Peanuts continues to be prevalent in multiple media through widespread syndication, the publication of The Complete Peanuts, the release of several new television specials (all of which Schulz had worked on, but had not finished, before his death), and Peanuts Motion Comics. Additionally, BOOM! Studios has published a series of comic books that feature new material by new writers and artists, although some of it is based on classic Schulz stories from decades past, as well as including some classic strips by Schulz, mostly Sunday color strips.

In early 2011, United Media (the parent of United Feature Syndicate) struck a distribution deal with Universal Uclick (now known as Andrews McMeel Syndication) for syndication of the company's 150 comic strip and news features, including Peanuts.[43][44][permanent dead link] On January 5, 2015, Universal Uclick's website, GoComics, announced on that it would be launching "Peanuts Begins", a feature rerunning the entire history of the strip from the beginning in colorized form. This was done to honor the 65th anniversary of the strip's debut.[45]

Characters

[edit]

Charlie Brown

[edit]Charlie Brown is a young boy. He is the main character, acting as the center of the strip's world and serving as an everyman.[46][47][48] While seen as decent, considerate, and reflective, he is also awkward, deeply sensitive, and said to suffer from an inferiority complex. Charlie Brown is a constant failure: he can never win a ballgame; he can never successfully fly a kite.[47][49] His sense of determination regardless of the certainty of failure can be interpreted as either self-defeating stubbornness or admirable persistence. When he fails, however, he experiences pain and anguish through self-pity.[49] The journalist Christopher Caldwell observed this tension between Charlie Brown's negative and positive attitudes, stating: "What makes Charlie Brown such a rich character is that he's not purely a loser. The self-loathing that causes him so much anguish is decidedly not self-effacement. Charlie Brown is optimistic enough to think he can earn a sense of self-worth."[50] Schulz named Charlie Brown after a colleague of his while working at Art Instruction, whose full name was Charlie Francis Brown.[51]

Readers and critics have explored the question as to whether Schulz based Charlie Brown on himself. This question often carried the suggestion that the emotionally sensitive and depressed behavior of Charlie Brown drew from Schulz's own life or childhood experiences.[52][53][54] Commenting on the tendency of these conclusions being drawn, Schulz said in a 1968 interview, "I think of myself as Charles Schulz. But if someone wants to believe I'm really Charlie Brown, well, it makes a good story."[55] He explained in another interview that the comic strip as a whole is a personal expression, and so it is impossible to avoid all the characters presenting aspects of his personality.[54] Biographer David Michaelis made a similar conclusion, describing Charlie Brown as simply representing Schulz's "wishy-washiness and determination".[56] Regardless, some profiles of Schulz confidently held that Charlie Brown was based on him. All and all, Charlie Brown is a purely wholesome character.[57]

Snoopy

[edit]Snoopy is a dog, who later in the development of the strip would be described as a beagle.[58] While generally behaving like a real dog and having a non-speaking role, he connects to readers through having human thoughts.[59][60] Despite acting like a real dog some of the time, Snoopy possesses many different anthropomorphic traits. Most notably, he frequently walks on his hind legs and is able to use tools, including his typewriter. He introduces fantasy elements to the strip by extending his identity through various alter egos. Many of these alter egos, such as a "world-famous" attorney, surgeon or secret agent were seen only once or twice.[61] His character is a mixture of innocence and egotism; he possesses childlike joy, while on occasion being somewhat selfish.[62][63] He has an arrogant commitment to his independence but is often shown to be dependent on humans.[61][62] Schulz was careful in balancing Snoopy's life between that of a real dog and that of a fantastical character.[64] While the interior of Snoopy's small doghouse is described in the strip as having such things as a library and a pool table and being adorned with paintings of Wyeth and Van Gogh, it was never shown: it would have demanded an inappropriate kind of suspension of disbelief from readers.[65]

Linus and Lucy

[edit]Linus and Lucy are siblings; Linus is the younger brother, and Lucy is the older sister.[66]

Lucy is bossy, selfish and opinionated, and she often delivers commentary in an honest albeit offensive and sarcastic way.[67][68] Schulz described Lucy as full of misdirected confidence, but having the virtue of being capable of cutting right down to the truth.[69] He said that Lucy is mean because it is funny, particularly because she is a girl: he posited that a boy being mean to girls would not be funny at all, describing a pattern in comic strip writing where it is comical when supposedly weak characters dominate supposedly strong characters.[70] Lucy at times acts as a psychiatrist and charges five cents for psychiatric advice to other characters (usually Charlie Brown) from her "psychiatric booth", a booth parodying the setup of a lemonade stand.[71] Lucy's role as a psychiatrist has attracted attention from real-life individuals in the field of psychology; the psychiatrist Athar Yawar playfully identified various moments in the strip where her activities could be characterized as pursuing medical and scientific interests, commenting that "Lucy is very much the modern doctor".[49]

Linus is Charlie Brown's most loyal and uplifting friend and introduces intellectual, spiritual and reflective elements to the strip. He offers opinions on topics such as literature, art, science, politics and theology. He possesses a sense of morality and ethical judgment that enables him to navigate topics such as faith, intolerance, and depression. Schulz enjoyed the adaptability of his character, remarking he can be "very smart" as well as "dumb".[72] He has a tendency of expressing lofty or pompous ideas that are quickly rebuked.[67] He finds psychological security from thumb sucking and holding a blanket for comfort. The idea of his "security blanket" originated from Schulz's own observation of his first three children, who carried around blankets. Schulz described Linus's blanket as "probably the single best thing that I ever thought of". He was proud of its versatility for visual humor in the strip, and with how the phrase "security blanket" entered the dictionary.[73][74]

Peppermint Patty and Marcie

[edit]Peppermint Patty and Marcie are two girls who are friends. They attend a different school than Charlie Brown, on the other side of town, and so represent a slightly different social circle from the other characters.[75]

Peppermint Patty is a tomboy who is forthright and loyal and has what Schulz described as a "devastating singleness of purpose".[76] She frequently misunderstands things, to the extent that her confusion serves as the premise of many individual strips and stories; in one story she prepares for a "skating" competition, only to learn with disastrous results that it is for roller skating and not ice skating.[77] She struggles at school and with her homework and often falls asleep in school. The wife of Charles Schulz, Jean Schulz, suggested that this is the consequence of how Peppermint Patty's single father works late; she stays awake at night waiting for him. In general, Charles Schulz imagined that some of her problems were from having an absent mother.[78]

Marcie is bookish and a good student.[75] Schulz described her as relatively perceptive compared to other characters, stating that "she sees the truth in things"[76] (although she perpetually addresses Peppermint Patty as "sir"). The writer Laura Bradley identified her role as "the unassuming one with sage-like insights".[79]

Supporting characters

[edit]In addition to the core cast, other characters appeared regularly for a majority of the strip's duration:

- Sally Brown is the younger sister of Charlie Brown. She has a habit of fracturing the English language to comical effect.[80] She reacts negatively to school and homework due to dealing with dogmatic memorization and obeying ambiguous instructions. She otherwise confidently delivers speeches in oral exams, using wordplay and puns while framing her topics with theatrics and suspense.[81]

- Schroeder is a boy who is fanatic about Beethoven. In this relatively innocent role, he serves as an outlet for the expressions of other characters.[82] He most recognizably appears in the strip playing music on his toy piano,[83][84] as the catcher on Charlie Brown's baseball team and the romantic foil to Lucy's unrequited affections.

- Pig-Pen is a boy who is physically dirty, normally appearing with a cloud of dust surrounding him. Schulz acknowledged that the scope of his role is limited, but he continued to make appearances because of his popularity with readers.[85]

- Franklin is an African American boy who first appeared at the suggestion of a reader following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Since it was Schulz's intention to achieve this without being patronizing, he is a relatively normal character who mainly reacts to the oddness of other characters.[28]

- Woodstock is a bird and Snoopy's friend. He entirely communicates through peeps, forcing readers to guess what he says.[86] Schulz said that Woodstock is aware that he is small and inconsequential, a role that serves as lighthearted existential commentary on coping with the much larger world.[87]

- Spike is Snoopy's brother who lives alone in the California desert.[88]

Several early characters faded out of prominence during the strip's run. For example Shermy, Patty and Violet were core characters during the initial years of the strip.[89][90][91] By 1956, Patty and Violet's roles were described only as an extension to Lucy's, and Shermy, who was initially Charlie Brown's closest friend, was then described merely as "an extra little boy".[73] In 1954, Schulz attempted to introduce Charlotte Braun, who was essentially a female version of Charlie Brown but with an excessively loud voice; poor reaction to her humorless personality led to Schulz "killing her off" in a tongue-in-cheek letter to a fan in 1955.[92] Similarly Frieda, a girl with "naturally curly hair", was introduced in 1962, but was already being phased out by the late 1960s after her comic value had seemed to have rapidly run its course; and after 1975, she made only background appearances.[11] Conversely, Rerun, the youngest brother of Linus and Lucy, had only limited visibility after his introduction in 1973, but became a foreground character by the middle of the 1990s.[93]

Reception

[edit]Schulz received the National Cartoonists Society Humor Comic Strip Award for Peanuts in 1962, the Reuben Award in 1955 and 1964 (the first cartoonist to receive the honor twice), the Elzie Segar Award in 1980, and the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award in 1999. A Charlie Brown Christmas won a Peabody Award and an Emmy; Peanuts cartoon specials have received a total of two Peabody Awards and four Emmys. For his work on the strip, Schulz has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (as does Snoopy) and a place in the William Randolph Hearst Cartoon Hall of Fame. Peanuts was featured on the cover of Time on April 9, 1965, with the accompanying article calling it "the leader of a refreshing new breed that takes an unprecedented interest in the basics of life."[94]

The strip was declared second in a list of the "greatest comics of the 20th century" commissioned by The Comics Journal in 1999.[95] The top-ranked comic was George Herriman's Krazy Kat, a strip Schulz admired (and in fact was among his biggest inspirations), and he accepted the ranking in good grace, to the point of agreeing with it.[96] In 2002 TV Guide declared Snoopy and Charlie Brown tied for 8th[97] in its list of the "Top 50 Greatest Cartoon Characters of All Time",[98] published to commemorate its 50th anniversary.

Schulz was included in the touring exhibition "Masters of American Comics". His work was described as "psychologically complex", and his style as "perfectly in keeping with the style of its times."[21]

Despite the widespread acclaim Peanuts has received, some critics have alleged a decline in quality in the later years of its run, as Schulz frequently digressed from the more cerebral socio-psychological themes that characterized his earlier work in favor of lighter, more whimsical fare. For example, in an essay published in the New York Press at the time of the final daily strip in January 2000, "Against Snoopy", Christopher Caldwell argued that Snoopy, and the strip's increased focus on him in the 1970s, "went from being the strip's besetting artistic weakness to ruining it altogether".[23]

Legacy

[edit]Among cartoonists

[edit]Many cartoonists who came after Schulz have cited his work as an influence, including Lynn Johnston, Patrick McDonnell, and Cathy Guisewite,[99] the latter of whom stated, "A comic strip like mine would never have existed if Charles Schulz hadn't paved the way".[100]

The December 1997 issue of The Comics Journal featured an extensive collection of testimonials to Peanuts. Over 40 cartoonists, from mainstream newspaper cartoonists to underground, independent comic artists, shared reflections on the power and influence of Schulz's art. Gilbert Hernandez wrote, "Peanuts was and still is for me a revelation. It's mostly from Peanuts where I was inspired to create the village of Palomar in Love and Rockets. Schulz's characters, the humor, the insight ... gush, gush, gush, bow, bow, bow, grovel, grovel, grovel ..." Tom Batiuk wrote: "The influence of Charles Schulz on the craft of cartooning is so pervasive it is almost taken for granted." Batiuk also described the depth of emotion in Peanuts: "Just beneath the cheerful surface were vulnerabilities and anxieties that we all experienced, but were reluctant to acknowledge. By sharing those feelings with us, Schulz showed us a vital aspect of our common humanity, which is, it seems to me, the ultimate goal of great art."[101]

Cartoon tributes have appeared in other comic strips since Schulz's death in 2000 and are now displayed at the Charles Schulz Museum.[102] On May 27, 2000, many cartoonists collaborated to include references to Peanuts in their strips. Originally planned as a tribute to Schulz's retirement, after his death that February it became a tribute to his life and career. Similarly, on October 30, 2005, several comic strips again included references to Peanuts and specifically the It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown television special. On November 26, 2022, several cartoonists included references to Peanuts and Charles Schulz in their strips to celebrate his 100th birthday.[103]

In broader culture

[edit]Robert L. Short interpreted certain themes and conversations in Peanuts as consistent with parts of Christian theology and used them as illustrations in his lectures on the gospel, as explained in his book The Gospel According to Peanuts, the first of several he wrote on religion, Peanuts, and popular culture.

Giant helium balloons of Snoopy, Charlie Brown, and Woodstock have been featured in the annual Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York City since 1968. This was referenced in a 2008 Super Bowl XLII commercial for Coca-Cola, in which the Charlie Brown balloon snags a Coca-Cola bottle from two battling balloons (Underdog and Stewie Griffin). The Snoopy balloon appeared outside the window of Leonard Bernstein's Central Park West apartment in a scene in the movie Maestro, released in 2023.[104]

Snoopy has been the personal safety mascot for NASA astronauts since 1968,[105] and NASA issues a Silver Snoopy award to its employees or contractors' employees who promote flight safety. The black-and-white communications cap carrying an audio headset worn since 1968 by the Apollo, Skylab, and Space Shuttle astronauts was commonly referred to as a Snoopy cap.[106]

The Apollo 10 lunar module's call sign was Snoopy, and the command module's call sign was Charlie Brown.[107] While not included in the mission logo, Charlie Brown and Snoopy became semi-official mascots for the mission.[108][109] Charles Schulz drew an original picture of Charlie Brown in a spacesuit that was hidden aboard the craft to be found by the astronauts once they were in orbit. This drawing is now on display at the Kennedy Space Center.

The name of the Brazilian rock band Charlie Brown Jr., formed in 1992, is named after the character Charlie Brown. The idea came about when Chorão, the band's lead singer, ran over a coconut water stand where there was an image of the character printed on the facade of the establishment.[110]

Peanuts on Parade is St. Paul, Minnesota's tribute to Peanuts.[111] It began in 2000, with the placing of 101 five-foot-tall (1.5 m) statues of Snoopy throughout the city of Saint Paul. The statues were later auctioned at the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota. In 2001, there was "Charlie Brown Around Town", 2002 brought "Looking for Lucy", and in 2003, "Linus Blankets Saint Paul".[112] Permanent bronze statues of the Peanuts characters are found in Landmark Plaza in downtown St. Paul.[113]

Peanuts characters, and Charles Schulz have been recognized several times in U.S. commemorative postage stamps. A Peanuts World War I Flying Ace U.S. stamp was released on May 17, 2001. The value was 34 cents, first class.[114] A Charlie Brown Christmas forever stamp was issued on Oct. 2, 2015.[115] In 2022, the U.S. Postal Service commemorated the 100th anniversary of Schulz's birth with postage stamps honoring him "alongside his beloved characters".[116]

In 2001, the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors renamed the Sonoma County Airport, located a few miles northwest of Santa Rosa, California, the Charles M. Schulz Airport in his honor. The airport's logo features Snoopy as the World War I Flying Ace (goggles/scarf), taking to the skies on top of his red doghouse (the Sopwith Camel). A bronze statue of Charlie Brown and Snoopy stands in Depot Park in downtown Santa Rosa.[117]

Books

[edit]The Peanuts characters have been featured in many books over the years.[118][119] Some represented chronological reprints of the newspaper strip, while others were thematic collections such as Snoopy's Tennis Book, or collections of inspirational adages such as Happiness Is a Warm Puppy. Some single-story books were produced, such as Snoopy and the Red Baron. In addition, many of the animated television specials and feature films were adapted into book form.

The primary series of reprints was published by Rinehart & Company (later Holt, Rinehart and Winston) beginning in 1952, with the release of a collection simply titled Peanuts. This series, which presented the strips in rough chronological order (albeit with many strips omitted from each year) continued through the 1980s, after which reprint rights were handed off to various other publishers. Ballantine Books published the last original series of Peanuts reprints, including Peanuts 2000, which collected the final year of the strip's run.

Coinciding with these reprints were smaller paperback collections published by Fawcett Publications. Drawing material from the main reprints, this paperback series began with The Wonderful World of Peanuts in 1962 and continued through Lead On, Snoopy in 1992.

Charles Schulz had always resisted republication of the earliest Peanuts strips, as they did not reflect the characters as he eventually developed them. However, in 1997 he began talks with Fantagraphics Books to have the entire run of the strip, which would end up with 17,897 strips in total, published chronologically in book form.[120] In addition to the post-millennium Peanuts publications are BOOM! Studios restyling of the comics and activity books, and "First Appearances" series. Its content is produced by Peanuts Studio, subsequently an arm of Peanuts Worldwide LLC.

The Complete Peanuts

[edit]The entire run of Peanuts, covering nearly 50 years of comic strips, was reprinted in Fantagraphics' The Complete Peanuts, a 26-volume set published over a 12-year period, consisting of two years per volume published every May and October. The first volume (collecting strips from 1950 to 1952) was published in May 2004; the volume containing the final newspaper strips (including all the strips from 1999 and seven strips from 2000, along with the complete run of Li'l Folks[121]) was published in May 2016,[122] with a twenty-sixth volume containing outside-the-daily-strip Peanuts material by Schulz appeared in the fall of that year. A companion series, titled Peanuts Every Sunday and presenting the complete Sunday strips in color (as the main Complete Peanuts books reproduce them in black and white only), was launched in December 2013; this series will run ten volumes, with the last expected to be published in 2022.

In addition, almost all Peanuts strips are now also authoritatively available online at GoComics.com (there are some strips missing from the digital archive). Peanuts strips were previously featured on Comics.com.

Anniversary books

[edit]Several books have been released to commemorate key anniversaries of Peanuts:

- 20th (1970) – Charlie Brown & Charlie Schulz — a tie-in with the TV documentary Charlie Brown and Charles Schulz that had aired May 22, 1969

- 25th (1975) – Peanuts Jubilee

- 30th (1980) – Happy Birthday, Charlie Brown

- 30th (1980) – Charlie Brown, Snoopy and Me

- 35th (1985) – You Don't Look 35, Charlie Brown

- 40th (1990) – Charles Schulz: 40 Years of Life & Art

- 45th (1995) – Around the World in 45 Years

- 50th (2000) – Peanuts: A Golden Celebration

- 50th (2000) – 50 Years of Happiness: A Tribute to Charles Schulz

- 60th (2009) – Celebrating Peanuts[123]

- 65th (2015) – Celebrating Peanuts: 65 Years

Adaptations

[edit]Animation

[edit]

The strip was first adapted into animation in The Tennessee Ernie Ford Show. A TV documentary, A Boy Named Charlie Brown (1963), featured newly animated segments but this did not air due to not being able to find a channel willing to broadcast it.[124] It did however shape the team for A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965), a half-hour Christmas special broadcast on CBS. It was met with extensive critical success.[125] It was the first of a set of Peanuts television specials (second counting the 1963 documentary), and forms a selection of holiday-themed specials which are aired annually in the US to the present day,[126][127] including It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown[128] (1966), and A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving[129] (1973). The animated specials were significant to the cultural impact of Peanuts; by 1972, they were remarked as being "among the most consistently popular television specials" and "regularly have been in the top 10 in the ratings".[130] Many of the specials were acquired by Apple TV+ in 2020.[131] The first feature-length film, A Boy Named Charlie Brown, came in 1969,[132] and was one of four which were produced before the comic strip ended. A Saturday morning television series aired in 1983, each episode consisting of three or four segments dealing with plot lines from the strip.[133] An additional spin-off miniseries, This Is America, Charlie Brown, aired in 1988, exploring the history of the United States.[134]

The characters continue to be adapted into animation after the comic strip ended in 2000, with the latest television special Welcome Home, Franklin made in 2024. [135][needs update] A series of cartoon shorts premiered on iTunes in 2008, Peanuts Motion Comics, which directly lifted themes and plot lines from the strip.[136] In 2014, the French network France 3 debuted Peanuts by Schulz, a series of episodes each consisting of several roughly one-minute shorts bundled together.[137] The latest feature-length film, The Peanuts Movie, was released in 2015 by 20th Century Fox and Blue Sky Studios.[138] Two Peanuts Apple TV+ series, Snoopy in Space and The Snoopy Show, both premiered in 2019 and 2021, respectively.[139][140][141][142] The characters also make a guest appearance in Mariah Carey's Magical Christmas Special in 2020.[143] On November 6, 2023, a new feature film from WildBrain and Peanuts Worldwide was announced by Apple TV+. Charlie Brown, Snoopy and the gang will embark on an adventure in the Big City. Production starts in 2024.[144][145]

Series

- Peanuts animated specials (1965–present)

- The Charlie Brown and Snoopy Show (1983–1985)

- This Is America, Charlie Brown (1988–1989)

- Peanuts Motion Comics (2008)

- Peanuts (2014–2016)

- Snoopy in Space (2019–2021)

- The Snoopy Show (2021–2023)

Film

- A Boy Named Charlie Brown (1969)

- Snoopy Come Home (1972)

- Race for Your Life, Charlie Brown (1977)

- Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (and Don't Come Back!!) (1980)

- The Peanuts Movie (2015)

Music

[edit]The album A Charlie Brown Christmas was recorded in 1965, the original soundtrack from the animated television special of the same name.[146] It was performed by the jazz trio led by pianist Vince Guaraldi.[147] It enjoys enduring critical, commercial, and cultural success; employing a sombre and whimsical style, songs such as Christmas Time Is Here evoke a muted and quiet melody,[147] and arrangements such as the traditional carol O Tannenbaum improvised in a light, off-center pace.[146] The album has continued popularity to the present day; writer Chris Barton for the Los Angeles Times praised it in 2013 as "one of the most beloved holiday albums recorded",[146] and Al Jazeera described it as "one of the most popular Christmas albums of all time".[148] The album was added to the national recording registry of the Library of Congress in 2012, being regarded as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically important".[146]

The American rock band The Royal Guardsmen recorded four novelty songs from 1966 to 1968 as tributes to Snoopy. The first song was released as the single Snoopy Vs. The Red Baron (1966), based on the storyline of Snoopy sitting atop his dog house imagining himself as a World War I pilot, battling the German flying ace The Red Baron. The band would later release two more similar songs in 1967, Return of The Red Baron and Snoopy's Christmas. In 1968 they recorded Snoopy for President.[149]

Theater

[edit]

The characters first appeared in live stage production in 1967 with the musical You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown, scored by Clark Gesner. It is a collection of musical sketches, where the characters explore their identities and discover the feelings they have for each other.[150] The play was performed off-broadway, as well as later being performed as a live telecast on NBC.[130] The play continued to have other professional performances, in the London West End, and later a Broadway revival, while also being a popular choice of musical by amateur theater groups such as schools.[151]

A second musical premiered in 1975, Snoopy! The Musical, scored by Larry Grossman with lyrics by Hal Hackady. A sequel to You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown, Snoopy! is also a collection of musical sketches, though focused on Snoopy.[150] It was first performed in San Francisco,[152] and eventually off-Broadway for 152 performances.[153]

You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown and Snoopy!!! The Musical were both further adapted as animated television specials, respectively, in 1985[154] and in 1988.[150] Going in the opposite direction from animation to live production, is the 2016 A Charlie Brown Christmas, based on the animated television special of the same name. It is considered a generally faithful readaptation, although it features the additional characters Woodstock and Peppermint Patty who did not exist in the strip when the original was made.[155]

Licensing

[edit]Advertising and retail

[edit]

The characters from the comic have long been licensed for use on merchandise, the success of the comic strip helping to create a market for such items. In 1958, the Hungerford Plastics Corporation created a set of five vinyl dolls of the most famous characters (Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Lucy, Linus, and Schroeder); they expanded this line in 1961 to make the dolls slightly larger and included Sally and Pig-Pen.[156] An early example of the characters appearing in promotional material was strips and illustrations drawn by Schulz for the 1955 instructional booklet for the Kodak Brownie camera, The Brownie Book of Picture Taking.[157] Another early campaign was on behalf of Ford Motor Company; magazine illustrations, brochure illustrations, and animated television spots featuring the characters were used to promote the Ford Falcon from January 1960 into 1964.[157] Schulz credited the Ford campaign as the first time where licensing the characters earned "a lot of money". However, he expressed a dislike of illustrating the adverts, describing it as "hard work" and would have preferred to dedicate equivalent effort to drawing the Sunday format strips.[158]

Some licensing relationships were maintained long-term. Hallmark began printing greetings cards and party goods featuring the characters in 1960.[2] In the late 1960s, Sanrio held the licensing rights in Japan for Snoopy. Sanrio is best known for Hello Kitty and its focus on the kawaii segment of the Japanese market.[159] Beginning in 1985, the characters were made mascots and served as spokespeople for the MetLife insurance company, with the intention to make the business "more friendly and approachable".[160] Schulz justified the licensing relationship with MetLife as necessary to financially support his philanthropic work, although refused to openly describe the exact details of the work he was financing.[161] In 2016, the 31-year licensing relationship with MetLife ended.[160] The relationship resumed in 2023 with Snoopy returning as a mascot for pet insurance.[162]

In 1999, it was estimated that there were 20,000 different new products each year adorning a variety of licensed items, such as: clothing, plush toys of Snoopy, Thermos bottles, lunch boxes, picture frames, and music boxes.[2] The familiarity of the characters also proved lucrative for advertising material in both print and television,[163] appearing on products such as Dolly Madison snack cakes, Chex Mix snacks, Bounty paper towels, Kraft macaroni cheese and A&W Root Beer.[164]

The sheer extent to which the characters are used in licensed material is a subject of criticism against Schulz. Los Angeles Times pointed out that "some critics [say] Schulz was distracted by marketing demands, and his characters had become caricatures of themselves by shilling for Metropolitan Life Insurance, Dolly Madison cupcakes and others."[165] Schulz reasoned that his approach to licensing was in fact modest, stating "our [licensing] program is built upon characters who are figuratively alive" and "we're not simply stamping these characters out on the sides of products just to sell products" while also adding "Snoopy is so versatile he just seems to be able to fit into any role and it just works. It's not that we're out to clutter the market with products. In fact anyone saying we're overdoing it is way off base because actually we are underdoing it".[166]

Games

[edit]The Peanuts characters have appeared in several video games, such as Snoopy in 1984 by Radarsoft, Snoopy: The Cool Computer Game by The Edge, Snoopy and the Red Baron for the Atari 2600, Snoopy's Silly Sports Spectacular (1989, Nintendo Entertainment System), Snoopy's Magic Show (1990, Game Boy), Snoopy Tennis (2001, Game Boy Color), Snoopy Concert which was released in 1995 and sold to the Japanese market for the Super NES, and in October 2006, a second game titled Snoopy vs. The Red Baron by Namco Bandai for the PlayStation 2. In July 2007, the Peanuts characters appeared in the Snoopy the Flying Ace mobile phone game by Namco Networks. In November 2015, Snoopy's Town Tale was launched for mobile by Pixowl, featuring the entire Peanuts gang along with Snoopy and Charlie Brown.

In 1980 (with a new edition published in 1990), the Funk & Wagnalls publishing house also produced a children's encyclopedia called the Charlie Brown's 'Cyclopedia. The 15-volume set features many of the Peanuts characters.

In April 2002, The Peanuts Collectors Edition Monopoly board game was released by USAopoly. The game was dedicated to Schulz in memory of his passing.

Amusement parks

[edit]

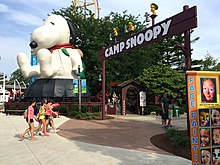

In 1983, Knott's Berry Farm, in Southern California, was the first theme park to license the Peanuts characters, creating the first Camp Snoopy area and making Snoopy the park's mascot. Knott's expanded its operation in 1992 by building an indoor amusement park in the Mall of America, called Knott's Camp Snoopy. The Knott's theme parks were acquired by the national amusement park chain Cedar Fair Entertainment Company in 1997, which continued to operate Knott's Camp Snoopy park until the mall took over its operation in March 2005.[167] Cedar Fair had already licensed the Peanuts characters for use in 1992 as an atmosphere,[168] so its acquisition of Knott's Berry Farm did not alter the use of those characters.

Snoopy is currently the official mascot of all the Cedar Fair parks. It was previously used in all of the park logos but it has since been removed. Cedar Fair also operated a Camp Snoopy area at Dorney Park & Wildwater Kingdom, Worlds of Fun, and Valleyfair featuring various Peanuts-themed attractions until 2011. There is still a Camp Snoopy area at Cedar Point and Knott's Berry Farm.

In 2008, Cedar Point introduced Planet Snoopy, a children's area where Peanuts Playground used to be. This area consists of family and children's rides relocated from Cedar Point's sister park Geauga Lake after its closing. The rides are inspired by Peanuts characters. The area also consists of a "Kids Only" restaurant called Joe Cool Cafe (there is a small menu for adults). In 2010, the Nickelodeon Central and Nickelodeon Universe areas in the former Paramount Parks (California's Great America, Canada's Wonderland, Carowinds, Kings Dominion, and Kings Island) were replaced by Planet Snoopy. In 2011, Cedar Fair announced it would also add Planet Snoopy to Valleyfair, Dorney Park & Wildwater Kingdom, and Worlds of Fun, replacing the Camp Snoopy areas. ″Carowinds″ Planet Snoopy was rethemed to Camp Snoopy. Planet Snoopy is now at every Cedar Fair parks beside Knott's Berry Farm, Carowinds, Michigan's Adventure.

Also, the Peanuts characters can be found at Universal Studios Japan in the Universal Wonderland section along with the characters from Sesame Street and Hello Kitty,[169] and in the Snoopy's World in Hong Kong.

Exhibition

[edit]An exhibition titled Good Grief, Charlie Brown! Celebrating Snoopy and the Enduring Power of Peanuts opened at Somerset House in London on 25 October 2018, running until 3 March 2019. The exhibition brought together Charles M. Schulz's original Peanuts cartoons with work from a wide range of acclaimed contemporary artists and designers who have been inspired by the cartoon.[170]

There is a trail called A Dog's Trail Across Cardiff, Caerphilly and Porthcawl. The trail features Snoopy from Peanuts.[171]

Ownership

[edit]On June 3, 2010, United Media sold all its Peanuts-related assets, including its strips and branding, to a new company, Peanuts Worldwide LLC, a joint venture of the Iconix Brand Group (which owned 80 percent) and Charles M. Schulz Creative Associates (20 percent). In addition, United Media sold its United Media Licensing arm, which represents licensing for its other properties, to Peanuts Worldwide.[172][173] United Feature Syndicate continued to syndicate the strip, until February 27, 2011, when Universal Uclick took over syndication, ending United Media's 60-plus-year stewardship of Peanuts.[174]

In May 2017, Canada-based DHX Media (now WildBrain) announced that it would acquire Iconix's entertainment brands, including the 80% stake of Peanuts Worldwide and full rights to the Strawberry Shortcake brand, for $345 million.[175] DHX officially took control of the properties on June 30, 2017.[176]

On May 13, 2018, DHX announced it had reached a strategic agreement in which Sony Music Entertainment Japan (whose consumer products division has been a licensing agent for the Peanuts brand since 2010) would acquire 49% of its 80% stake in Peanuts Worldwide for $185 million, with DHX holding a 41% stake and SMEJ owning 39%.[177] The transaction was completed on July 23.[178] Two months after the sale's completion, DHX eliminated the rest of its debt by signing a five-year, multi-million-dollar agency agreement with CAA-GBG Global Brand Management Group (a brand management joint venture between Creative Artists Agency and Hong Kong-based Global Brands Group) to represent the Peanuts brand in China and the rest of Asia excluding Japan.[179][180][181]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bethune 2007.

- ^ a b c Boxer 2000.

- ^ Podger 2000.

- ^ Walker 2002, p. [page needed].

- ^ The Peanuts Movie. Retrieved September 13, 2024 – via movies.disney.com.

- ^ The World Encyclopedia of Comics, edited by Maurice Horn, published in 1977 by Avon Books

- ^ "comic strip :: The first half of the 20th century: the evolution of the form". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ Yoe, Craig, Clean Cartoonists' Dirty Drawings. San Francisco, Calif.: Last Gasp, 2007, p. 36; Michaelis, David, Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography. New York: HarperPerennial, 2008, p. ix.

- ^ a b Inge 2000, p. 146.

- ^ Bang 2004, p. 5.

- ^ a b Inge 2000, p. 171.

- ^ Michaelis 2007, p. 218.

- ^ Michaelis 2007, p. 219.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 56.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 87.

- ^ Michaelis 2007, p. 221.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 216.

- ^ Michaelis 2007, p. 220.

- ^ Schulz, Charles (w, a). Peanuts. October 4, 1950, United Feature Syndicate.

- ^ Nat Gertler (October 2000). "Dale Hale and the 'Peanuts' Comic Book: The Interview". Hogan's Alley. No. 8. Cartoonician.com. Republished in Hogan's Alley blog Archived September 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine by Tom Heintjes, May 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Masters of American Comics John Carlin Yale University Press 2005

- ^ Tom Heintjes (May 17, 2015). "Charles M. Schulz on Cartooning | Hogan's Alley". Cartoonician.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ a b Caldwell, Christopher (January 4, 2000). "Against Snoopy". New York Press.

- ^ "Peanuts by Charles Schulz, August 22, 1966 Via @GoComics". GoComics. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Peanuts by Charles Schulz, October 10, 1965 Via @GoComics". GoComics. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Peanuts by Charles Schulz, March 06, 1961 Via @GoComics". GoComics. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Peanuts by Charles Schulz, July 29, 1968 Via @GoComics". GoComics. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Gertler 2012.

- ^ Evon, Dan (December 24, 2015). "You're a Racist, Charlie Brown?: A closer look at allegations of racism in the comic strip 'Peanuts'". Snopes.com.

- ^ "Charles M. Schulz".

- ^ "Peanuts by Charles Schulz, May 20, 1962 Via @GoComics". GoComics. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Peanuts by Charles Schulz, September 30, 1963 Via @GoComics". GoComics. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Peanuts by Charles Schulz, October 01, 1963 Via @GoComics". GoComics. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Peanuts by Charles Schulz, October 20, 1963 Via @GoComics". GoComics. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Lind, Stephen J., Reading Peanuts: The Secular and the Sacred, ImageTexT, retrieved August 31, 2010

- ^ Cronin, Brian (January 11, 2013). "Comic Book Legends Revealed #401". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ "About Al". Al Plastino (official site). Archived from the original on July 7, 2011.

- ^ "Most Syndicated Comic Strip, Peanuts, Charles Schulz, USA". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved June 9, 2007.

- ^ https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/2000/01/02 [bare URL]

- ^ https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/2000/01/09 [bare URL]

- ^ https://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/2000/01/16 [bare URL]

- ^ AP (May 28, 2000). "Comic strips hail spark of 'Peanuts' creator". Deseret News. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- ^ "Universal Uclick to Provide Syndicate Services for United Media". PR Newswire. February 24, 2011.

- ^ "United Media Outsources Content to Universal Uclick". Editor & Publisher. April 29, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "New Comic Alert! Peanuts Begins by Charles Schulz". GoComics. January 5, 2015. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ Boxer 2015.

- ^ a b Eco 1985.

- ^ Warner 2018.

- ^ a b c Yawar 2015.

- ^ Caldwell 2000.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 38.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 5.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 44.

- ^ a b Inge 2000, p. 66.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 62.

- ^ Michaelis 2007, p. 258.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 65.

- ^ Michaelis 2007, p. 387.

- ^ Michaelis 2007, p. 389.

- ^ Inge 2010, p. 172.

- ^ a b Michaelis 2007, p. 390.

- ^ a b Inge 2000, p. 59.

- ^ Michaelis 2007, p. 391.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 50.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 25.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 70.

- ^ a b Inge 2000, p. 47.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 196.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 52.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 45.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 89.

- ^ Michaelis 2007, pp. 252–253.

- ^ a b Inge 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 91.

- ^ a b Boylan 2019.

- ^ a b Inge 2010, p. 174.

- ^ Inge 2010, p. 94.

- ^ Schulz 2016.

- ^ Bradley 2015.

- ^ Inge 2010, p. 175.

- ^ Wong 2018.

- ^ Inge 2010, p. 82.

- ^ Michaelis 2007, p. 254.

- ^ Inge 2010, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 96.

- ^ Inge 2010, p. 171.

- ^ Inge 2010, p. 176.

- ^ "1929". Charles M. Schulz Museum. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Inge 2000, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Inge 2010, p. 7.

- ^ Goodwillie 2021.

- ^ "A Cartoon Death on Your Conscience". ABC News. September 4, 2000. Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- ^ Farago 2017, p. 241.

- ^ "Comics: Good Grief". TIME.com. April 9, 1965. Archived from the original on March 20, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Tom Spurgeon, Art Spiegelman, Bart Beatty et al., "The Top 100 English-Language Comics of the Century," The Comics Journal 210 (February 1999)

- ^ "Fantagraphics Books to publish "The Complete Peanuts" by Charles M. Schulz" (Press release). Fantagraphics. October 13, 2003. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Retrieved November 30, 2006.

- ^ "D'oh! Bugs Bunny Edges Out Homer Simpson" (Press release). TV Guide. July 26, 2002.

- ^ "Breaking News, U.S., World, Weather, Entertainment & Video News". Archives.cnn.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2005. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Walker 2002, p. 75.

- ^ Walker 2002, p. 106.

- ^ "'Dear Sparky ... ' Comic Artists From Across the Medium on the Legendary Cartoonist and Creator of Peanuts," The Comics Journal, December 1997

- ^ Hilton, Spud (September 29, 2002), "Peanuts fan blankets Sparky's Santa Rosa", San Francisco Chronicle, retrieved October 12, 2007

- ^ "Cartoonist Tributes #Schulz100". Charles M. Schulz Museum. November 26, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ Phillips, Michael (December 1, 2023). "'Maestro' review". Twin Cities. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ 10 Things You Didn't Know About Space Exploration, Usnews.com, retrieved October 12, 2007

- ^ "Learn About Spacesuits". NASA. November 13, 2008. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ "NEWSROOM for February 14, 2000", CNN, retrieved October 12, 2007

- ^ "Snoopy on Apollo 10". Archived from the original on October 25, 2007. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ^ "Charlie Brown and Snoopy at Apollo 10 Mission Control". Science.ksc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on June 19, 2001. Retrieved October 17, 2007.

- ^ "Acidente envolvendo cantor Chorão fere 4 pessoas". Estadão (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved August 3, 2024.

- ^ Karlson, Karl J. (June 29, 2000), "'Peanuts' coming to the riverfront", CNN, retrieved October 12, 2007

- ^ Linus Blankets St. Paul Archived May 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ten Great Places to Visit in Downtown Saint Paul, archived from the original on March 8, 2005, retrieved October 12, 2007

- ^ "Arago: Peanuts Comic Strip Issue". Arago.si.edu. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ "Charlie Brown Christmas Forever Stamps". U.S. Postal Service. September 30, 2015. Archived from the original on June 3, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ "Cartoonist Charles M. Schulz Honored Alongside His Beloved Characters With New Forever Stamps". about.usps.com. September 30, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Russell, Sabin (June 6, 2005), "No laughing matter: statue of 'Charlie Brown' missing", San Francisco Chronicle, retrieved October 12, 2007

- ^ "Our Peanuts book collectors guide". AAAUGH.com. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- ^ Bang, Derrick. "PEANUTS Reprint Books". Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ McKinnon, Heather (February 15, 2004). "Seattle's Fantagraphics Books will release 'The Complete Peanuts'". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ "The Complete Peanuts: 1999–2000". Fantagraphics Books. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ "THE COMPLETE PEANUTS 1955–1956". Snoopy. March 22, 2004. Archived from the original on September 24, 2005. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- ^ "Celebrating Peanuts". Andrewsmcmeel.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Mendelson 2000, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Bang 2012, p. 191.

- ^ Stevens 2008.

- ^ Bell 2018b.

- ^ Horn 2018.

- ^ Bell 2018a.

- ^ a b The Morning Record 1972.

- ^ Hardy 2020.

- ^ Canby 1969.

- ^ Murray 2013.

- ^ Solomon 1988b.

- ^ Davis 2022.

- ^ Warner Bros. 2008.

- ^ O'Brien 2014.

- ^ Rechtshaffen 2015.

- ^ Petski 2019.

- ^ Keller 2019.

- ^ Martoccio 2020.

- ^ Johnson 2021.

- ^ Arnold 2020.

- ^ Brew, Caroline (November 6, 2023). "Peanuts Head to the Big City in First Apple TV+ Movie". Variety. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ "Apple sets its first original Peanuts feature film, taking Snoopy and Charlie Brown on an epic adventure through the Big City". Apple TV+ Press. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Barton 2013.

- ^ a b Jackson 2016.

- ^ Maxwell 2014.

- ^ Theroux 2015.

- ^ a b c Solomon 1988a.

- ^ Willis & Hodges 2006.

- ^ Suskin 2000, p. 350.

- ^ Gans 2004.

- ^ DeMott 2010.

- ^ Jevens 2016.

- ^ Kidd & Spear 2015, p. 132.

- ^ a b Schulz & Groth 2016, p. 35.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 253.

- ^ Gomez 2004.

- ^ a b Hauser & Maheshwari 2016.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 254.

- ^ "MetLife Insurance Has a New Top Dog: Snoopy". MetLife. January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Elliott 2000.

- ^ Bankston 2000.

- ^ Tawa 2000.

- ^ Inge 2000, p. 103.

- ^ "Mall of America strikes deal with Nickelodeon for theme park", USA Today, March 7, 2007, retrieved October 12, 2007

- ^ Munarriz, Rick Aristotle (January 24, 2006), Is Pixar Worth $7 Billion to Disney?, retrieved October 12, 2007

- ^ "Charles M. Schulz MuseumVisiting Universal Studios Japan – Charles M. Schulz Museum". Schulzmuseum.org. October 30, 2013. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ "Good Grief, Charlie Brown!". Somerset House Trust. May 29, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ "The Snoopy trail has ended but here's how you can see them all in one place". June 7, 2022.

- ^ "Iconix Brand Group Closes Acquisition of Peanuts – NEW YORK, June 3 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/" (Press release). Prnewswire.com. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ "Iconix Forms Peanuts Worldwide | License! Global". Licensemag.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Cavna, Michael (September 11, 2010). "'Peanuts' comics strip will leave syndicate in February for Universal Uclick". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ "DHX Media Acquires 'Peanuts' in $345 Million Purchase of Iconix". Variety. May 10, 2017. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- ^ "DHX Media Closes Acquisition of Peanuts and Strawberry Shortcake". Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- ^ Ltd., DHX Media. "DHX Media Forms Strategic Partnership with Sony on Peanuts". www.prnewswire.com (Press release).

- ^ "DHX MEDIA CLOSES SALE TO SONY OF MINORITY STAKE IN PEANUTS – DHX Media". July 23, 2018.

- ^ "DHX Media shifts strategy toward digital as young viewers' TV habits change". Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ "DHX Announces Peanuts Deal, Content Refocus Following Strategic Review – Animation Magazine". www.animationmagazine.net. September 25, 2018.

- ^ Ltd., DHX Media. "DHX Media Concludes Strategic Review". www.prnewswire.com (Press release).

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Bang, Derrick, ed. (2004). Li'l Folks – Charles M. Schulz: Li'l Beginnings. Charles M. Schulz Museum. ISBN 9780974570914.

- Bang, Derrick (2012). Vince Guaraldi at the Piano. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5902-5.

- Farago, Andrew (2017). The Complete Peanuts Family Album. Weldon Owen. ISBN 978-1681882925.

- Inge, M. Thomas, ed. (2000). Charles M. Schulz: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578063055.

- Inge, M. Thomas, ed. (2010). My Life With Charlie Brown. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1604734478.

- Kidd, Chip; Spear, Geoff (2015). Only What's Necessary: Charles M. Schulz and the Art of Peanuts. New York: Abrams Comic Arts. ISBN 978-1-4197-1639-3.

- Mendelson, Lee (2000). A Charlie Brown Christmas: The Making of a Tradition. It Books. ISBN 978-0062272140.

- Michaelis, David (2007). Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography. Harper. ISBN 9780066213934.

- Schulz, Charles M. (2016). Groth, Gary (ed.). The Complete Peanuts, Vol. 26 1950-2000. Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 978-1-78211-973-9.

- Suskin, Steven (2000). Show tunes. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-512599-1.

- Walker, Brian (2002). The Comics: Since 1945. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-3481-7. OCLC 680428021.

Periodicals

[edit]- Bethune, Brian (October 22, 2007). "The Man Who Recalled Everything: Every Slight and Bitter Memory in Charles Schulz's Long Life Made Its Way into 'Peanuts'". Maclean's. Rogers Media. p. 61. ISSN 0024-9262. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- Boxer, Sarah (February 14, 2000). "Charles M. Schulz, 'Peanuts' Creator, Dies at 77". The New York Times. ISSN 1553-8095. Archived from the original on January 3, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- Canby, Vincent (December 5, 1969). "Screen: Good Old Charlie Brown Finds a Home". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Charlie Brown video shows consistently among leaders". The Morning Record. October 12, 1972. p. 20. LCCN sn87062255.

- Eco, Umberto (June 13, 1985) [1963]. "On 'Krazy Kat' and 'Peanuts'". The New York Review of Books. Translated by Weaver, William. ISSN 0028-7504. Essay first published in 1963, in the book Apocalittici e integrati (Italian; published by Bompiani)

- Gertler, Nat (2012). "Crossing the Color Line (in Black and White): Franklin in 'Peanuts'". Hogan's Alley. No. 18. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- Podger, Pamela J. (February 22, 2000). "Saying Goodbye / Friends and family eulogize cartoonist Charles Schulz". San Francisco Chronicle. ISSN 1932-8672. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- Solomon, Charles (January 29, 1988a). "Television Reviews : 'Snoopy' Musical Doesn't Live Up to Its Potential". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035.

- Solomon, Charles (October 21, 1988b). "TV REVIEW : Good Grief! The 'Peanuts' Gang and the Pilgrims Are a Poor Match". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035.

- Willis, John; Hodges, Ben (2006). "Harold Fielding (Obituary)". Theatre World, Vol. 60 (2003–2004). Applause Theatre and Cinema Books. p. 315. ISBN 1-55783-650-7. ISSN 1088-4564. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

Online

[edit]- Bell, Amanda (November 18, 2018a). "How to Watch A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving". TV Guide. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Bell, Amanda (November 19, 2018b). "How to Watch A Charlie Brown Christmas". TV Guide. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Horn, Alison (October 18, 2018). "How you can watch 'It's The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown'". ABC 10 News San Diego. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Murray, Noel (October 1, 2013). "The Charlie Brown And Snoopy Show: The Complete Animated Series". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Franich, Darren (November 24, 2011). "'Happiness is a Warm Blanket, Charlie Brown' is terrible. Will kids care?". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Stevens, Dana (October 31, 2008). "Good Grief: Why I love the melancholy Peanuts holiday specials". Slate. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Binazeski, Peter (November 3, 2008). "Good Grief! Linus and Charlie Brown Are Thrown into Election 2008 with New Short Form Videos Available for a Limited Time as a Free Download on iTunes" (Press release). Warner Brothers. Business Wire. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- O'Brien, Chris (December 25, 2014). "Peanuts comic will come to life in French TV series". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Rechtshaffen, Michael (November 2, 2015). "'The Peanuts Movie': Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Jevens, Darel (November 18, 2016). "Stage version gets the meaning of 'A Charlie Brown Christmas'". Chicago Sun Times. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Isherwood, Charles (February 4, 1999). "You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown". Variety. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- DeMott, Rick (January 25, 2010). "You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown". Animation World Network. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Gans, Andrew (January 26, 2004). "Sutton and Hunter Foster, Christian Borle and Ann Harada Set for All-Star Snoopy! Benefit Concert". Playbill. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Maxwell, Tom (December 24, 2014). "O come all ye fans of A Charlie Brown Christmas soundtrack". Al Jazeera. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Jackson, Reed (December 16, 2016). "How the Vince Guaraldi Trio's 'A Charlie Brown Christmas' Became the Soundtrack of the Holidays". Vice. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Barton, Chris (December 19, 2013). "Vince Guaraldi's 'A Charlie Brown Christmas' score is a gift". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Petski, Denise (September 27, 2019). "Apple Unveils Trailers For Kids' Series 'Helpsters', 'Snoopy In Space' & 'Ghostwriter'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Hauser, Christine; Maheshwari, Sapna (October 20, 2016). "MetLife Grounds Snoopy. Curse You, Red Baron!". The New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Elliott, Stuart (February 17, 2000). "Will 'Peanuts' characters remain effective images, or will they go the way of the Schmoo?". The New York Times. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Tawa, Rene (December 25, 2014). "Beloved 'Peanuts' creator Charles Schulz is mourned worldwide". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Bankston, John (February 13, 2000). "Goodbye, 'Peanuts'". The Augusta Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007.

- Gomez, Edward (July 14, 2004). "How Hello Kitty Came to Rule the World / With little advertising and no TV spinoff, Sanrio's 30-year-old feline turned cute into the ultimate brand". SF Gate. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Keller, Joel (November 2, 2019). "Stream It Or Skip It: 'Snoopy In Space' On Apple TV+, Where The Peanuts Gang Help Snoopy Explore The ISS And The Moon". Decider. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Theroux, Gary (December 18, 2015). "The Royal Guardsmen's Snoopy connection". Goldmine. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Yawar, Athar (October 3, 2015). "The madness of Charlie Brown". The Lancet. 386 (10001): 1332–1333. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00338-4. PMID 26460766.

- Handy, Bruce (August 29, 2019). "The Paradox of Peanuts". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Boxer, Sarah (November 2015). "The Exemplary Narcissism of Snoopy". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Warner, Kylie (November 6, 2018). "How Charlie Brown and Snoopy stole our hearts". 1843. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Schulz, Jean (November 9, 2016). "Peppermint Patty – a "rare gem"". Charles M. Schulz Museum. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Boylan, Jennifer Finney (February 21, 2019). "What "Peanuts" Taught Me About Queer Identity". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Bradley, Laura (November 12, 2015). "Peanuts' Most Fascinating Relationship Has Always Been Between Peppermint Patty and Marcie". Slate. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- Wong, Kevin (March 9, 2018). "Sally From Peanuts Made Me A Better Teacher". Kotaku. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- Martoccio, Angie (October 2, 2020). "Good Grief: Apple TV+ Celebrates 70 Years of 'Peanuts' With 'The Snoopy Show'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- Hardy, DC (October 19, 2020). "It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown and other Peanuts specials come to Apple TV+". Cult of Mac. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Arnold, Chuck (December 4, 2020). "Mariah Carey has sing-off with Ariana Grande, Jennifer Hudson in special". New York Post. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- Johnson, Kevin (February 4, 2021). "The appealing Snoopy Show may stretch viewers' love for the iconic dog". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- Goodwillie, Ian (February 22, 2021). "Peanuts: 10 Characters Who Disappeared Over The Years". CBR. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- Davis, Victoria (April 15, 2022). "'It's the Small Things, Charlie Brown' Celebrates Earth Day and the Schulz Legacy". Animation World Network. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Ray, Michael (November 23, 2023). "Peanuts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on January 30, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Peanuts at GoComics.com

- Peanuts Turns 60. Archived October 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine – slideshow by Life

- Peanuts (comic strip)

- 1950 comics debuts

- 1950 establishments in the United States

- 2000 comics endings

- 2000 disestablishments in the United States

- American comic strips

- American comics adapted into films

- Culture of the United States

- Child characters in comics

- Comic strips set in the United States

- Comics about children

- Comics about dogs

- Comics adapted into animated films

- Comics adapted into animated series

- Comics adapted into plays

- Comics adapted into television series

- Comics adapted into video games

- WildBrain franchises

- Gag-a-day comics

- Satirical comics

- Slice of life comics

- Sony Music Entertainment Japan franchises